The Beloretsk cast-iron smelting and ironworking plant was founded in 1762 by merchants I. B. Tverdyshov and I. S. Myasnikov. The first builders and workers of the plant were serfs from the Simbirsk, Arzamas, Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Alatyr, and other districts. The plant’s capacity reached 122.5 thousand poods of cast iron and 80 thousand poods of iron per year.

Because of the Pugachev Rebellion in 1773, the Beloretsk plant was devastated and burned, but three years later it was restored, and by 1777 the enterprise had practically returned to its former output, producing 110,131 poods of cast iron. In 1784 the plant changed owners: it passed to the eldest daughter of I. S. Myasnikov, who married the nobleman A. I. Pashkov and brought the Beloretsk plant as her dowry. By 1800, Beloretsk cast iron was of high quality and among the cheapest in the Urals, and Beloretsk iron, known as “Pashkov iron,” was famous for its easy forgeability and ductility.

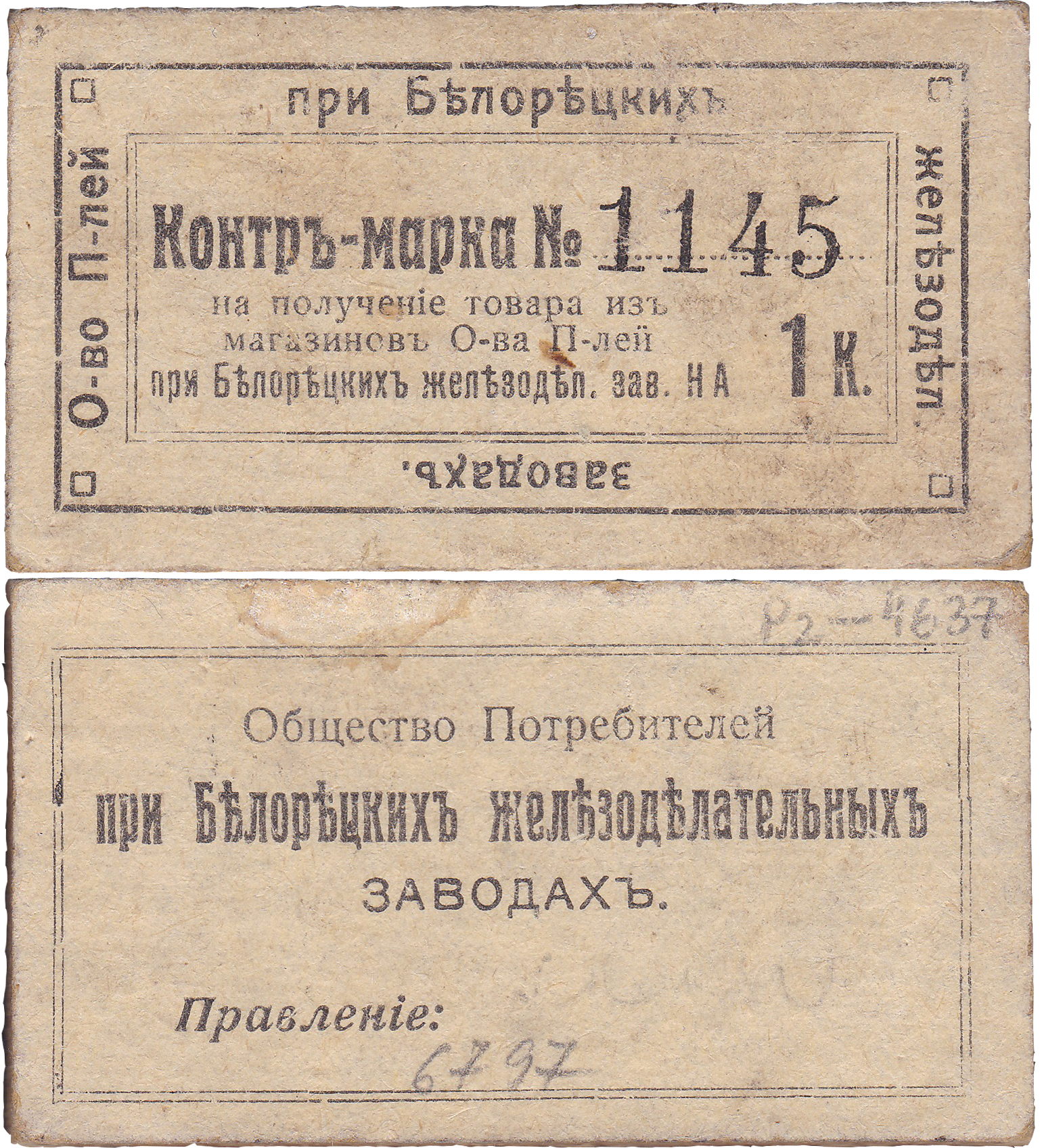

In 1866 the plant came under state trusteeship, and in 1874 the “Pashkovs’ Joint-Stock Company of the Beloretsk Ironworks” was established. The owner of the joint-stock company became the Moscow trading house “Vogau & Co.,” which began re-equipping the plant.

Vogau was a family of German entrepreneurs in 19th-century Russia. The dynasty was founded by Maximilian von Vogau: having come from Germany to Russia, he accepted Russian citizenship and married the daughter of the textile manufacturer Rabenek.

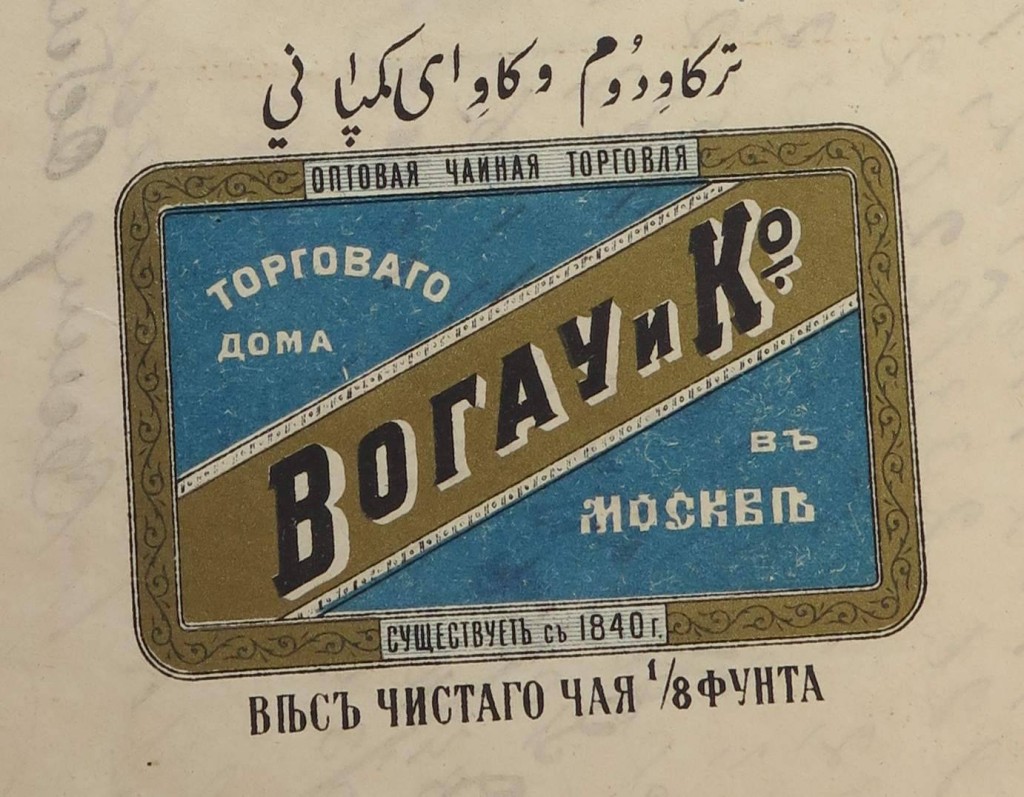

In 1840 the Vogau brothers became co-founders of an independent office for selling vat dyes, other chemical goods, and tea. This marked the beginning of the Vogau trading house.

For thirty years the Vogau brothers traded in vat dyes and chemical goods, and only from the early 1870s did they begin to enter the sphere of industrial production. They appeared as founders—either as principal owners or together with other capitalists—of the Beloretsk works company, partnerships of the Kolchugin plants producing copper, the Moscow Metal Plant, the Moscow Sugar Plant, and later the soda company “Lyubimov, Solvay & Co.,” and the tea partnership “Karavan.” The Vogaus participated in creating the Water Supply and Gas Supply Company, the partnership of Hubner and Ludwig Rabenek manufactories, the Moscow–Kazan Railway Company, the Russian Bank for Foreign Trade, and the Riga Commercial Bank.

The size of their capital allowed the Vogaus to take over enterprises that faced collapse. Often, for those businesses it was simply a спасение. Unfazed by temporary disorder in one firm or another, the trading house invested funds, helped them climb out of debt, put affairs in order, naturally subordinated the enterprise to itself, and began to earn profit.

In the end, the Vogaus became the de facto owners of 20 enterprises. They exerted their influence through acquiring blocks of shares, bonds, and partnership stakes, and through the direct participation of representatives of the family clan in the governing bodies of joint-stock companies and partnerships. Vogau securities owned by relatives and their closest circle amounted to a value exceeding 18 million rubles.

The most significant role in the diverse, sprawling, well-organized Vogau monopoly was played by four enterprises: the Beloretsk company, the Kolchugin partnership, the refined sugar plant company, and the “Karavan” partnership.

In the company “Lyubimov, Solvay & Co.” with capital of 10 million, the Vogaus owned only 16 percent of the shares; however, they sat on the board and held in their hands almost all soda sales.

A similar situation developed with the Moscow Cement Company and many other enterprises.

A leading place in Vogau activity was gradually taken by the tea trade through the “Karavan” company. In total they purchased and sold 600–620 thousand poods of tea for 35–40 million rubles per year. The total volumes were about one third of Russia’s tea trade.

A substantial income item remained “chemical” goods obtained from abroad, as well as import operations with cotton and nonferrous metals. Annual trade turnover exceeded 120 million rubles.

The foundation of the trading house’s growth, the initial source of accumulation of the Vogaus’ huge capital, was a small office for selling dyes that gradually expanded its activity with imported goods. At the next stage came trade in domestically produced goods, and then the move into industry began.

It should be borne in mind that the trading house, having accumulated large capital, also began to develop banking, engaging in crediting import trade and financing the enterprises it controlled. This is where the later paradoxical debts of the joint-stock company “Beloretsk Works,” owned by the Vogaus, to the Vogau trading house came from.

From 1865 the trading house had a representative in London, and in 1875 an office was created there. Over time the London office turned into a banking house that played an important role in saving Vogau capital during the “struggle against German dominance” that began during World War I, and then during the revolution and the civil war.

The London office concluded local deals with suppliers of imported goods and issued loans against the goods being purchased. English affairs until 1914 were managed by Albert Schumacher, the brother-in-law of Karl Vogau, the younger brother of the firm’s founder, Philipp Maksimovich.

To the great misfortune of the prosperous businessmen, in 1914 Germany and Russia found themselves the main opponents in the world war, and the Vogaus, among other things, were almost monopolists in copper trade—a strategic commodity. Society’s natural suspicion: how is it that we are at war with Germans, and they are here in Russia’s defense industry?! The general atmosphere in the country—wound up by losses, defeats, rumors of treason in the tsar’s entourage, and, in addition, the empress being German—was sharply anti-German.

Under these conditions, Black Hundred pogroms of German firms became possible, along with firms whose owners bore German surnames. On May 26–29, 1915, in Moscow, with the inaction and connivance of the authorities, tens of thousands of people smashed all firms and apartments of owners with German surnames. The crowd brutally dealt with the factory director Karlsen at the “Partnership of Emil Zindel’s Calico-Printing Manufactory,” and then it was the turn of Robert Schrader’s factory. After smashing it, the rioters headed to the owner’s house, where they did not spare women: the wife of managing director Jansen, his sister, his mother-in-law, and B. Engels, a Russian subject.

By various estimates, from 50 to 100 thousand “tramps” and “respectable gentlemen” took part in the pogroms. In any case, during the destruction of Vogau warehouses, in a crowd consisting mostly of workers, even policemen were seen, who also carried off goods. A significant part of the Vogau archives perished then.

During the pogroms, 475 trading enterprises and 207 apartments were damaged. The total amount of losses exceeded 50 million rubles.

A committee to “combat German dominance” was created under the government. By September 1916, a report by the Ministry of Trade and Industry was prepared for the Council of Ministers on the activities of the trading house “Vogau & Co.” and the need to liquidate its business.

The company’s management, seeking to preserve its existence, took a number of measures, to the point that immediately after the start of the war, board members without Russian citizenship hurried to obtain it. In 1914, Mark Moritz and Mark Hugo became full-fledged Russian citizens.

In one of their petitions, the Vogaus stated that in connection with the desire “to avoid any reproaches in the future, the trading house decided to refrain in the future from broad participation in the copper trade and did not renew with the joint-stock company ‘Copper’ the contract whose term expires on December 31, 1916.”

In the same vein was the sale of the company’s most important enterprises—the Kolchugin partnership and the Beloretsk company—to the Russo-Asiatic and International banks in May 1916.

A weighty voice came from Russia’s military ally, England. In Petrograd, the British ambassador spoke in support of “Vogau & Co.,” clearly at the effort of Walter Schumacher.

An extremely difficult moral and ethical situation developed for Germans. They had to prove that they were not working for the benefit of their ethnic homeland, that they were “their own” here, Russian. And it must be said they did this very tactfully, without losing dignity, without humiliating themselves with assurances and oaths of special devotion to the state that had sheltered them. Between the lines of all arguments one could read: yes, we are Germans, but we work in Russia and do our job honestly, responsibly, without causing any harm to the warring sides.

The measures taken bore fruit: in the Council of Ministers, key figures spoke against liquidating the trading house—the Minister of Trade and Industry Shakhovskoy and the Minister of Finance Bark. Particularly significant was the statement of Russia’s chief financier that liquidation would cost the treasury 30 million rubles.

Most likely, individual work was also carried out with senior officials. Deputy Minister of Trade and Industry Veselago, who had signed the report on the need to completely curtail the company’s activities, six days later at an interdepartmental meeting suddenly recognized Vogau activity in the copper industry as “useful” and “fully meeting the requirements of state defense.”

Through joint efforts, the company’s existence—though not without losses—was defended, but 1917 was already looming ahead.

The process of revolutionary change of ownership at the Beloretsk plant passed unnoticed and without pomp. The events of the last decade—and not only the last—had long prepared public consciousness for the fact that changes were inevitable. Trusteeship administration was a temporary measure; after the abolition of serfdom there was no talk of returning to Pashkov control, and the people of Beloretsk lived in expectation of change.

By the 1870s the trading house “Vogau & Co.” had gained confidence, stability, and financial solidity. The monetary base required new areas of application. The search for new sources of income was connected with the arrival in leadership in 1872–1873 of the founder’s sons-in-law—Konrad Karlovich Banz and, from Vogau’s younger brother, Moritz Filippovich Mark. They directed their attention to industrial production, believing that, besides trading offices and warehouses, it would be useful for the firm to have within its sphere of interests individual industrial enterprises distinguished by some unique qualities.

Having learned of the existence of the Beloretsk works, which were in difficult financial condition and a state of some uncertainty, the Vogaus conducted reconnaissance regarding the prospects of earning income. They clarified the essentials: the works had an excellent raw-material base, a name in sales markets, were provided with labor resources; delivery of products to the central regions of the country was difficult but feasible.

The Beloretsk works, it must be said, were very lucky that the attention came not from an ordinary firm, but from a wealthy one with sufficient free capital, extensive connections in trade and financial circles, and foreign operations. The Vogaus did not waste money, and if they were going to invest in an enterprise, it meant they knew it would certainly pay off.

A bankruptcy конкурс was established against the Pashkov property, and the estate was put up for sale. It was acquired by the trading house “Vogau & Co.” from the bankruptcy administration and then passed into the ownership of the newly established in 1874 Pashkovs’ Joint-Stock Company of the Beloretsk Ironworks with capital of 250,000 rubles. The company’s shares were entirely distributed among members of the trading house.

The enterprise was far away, aside from transportation routes—at that time the Samara–Zlatoust railway did not yet exist, and the nearest point was Orenburg, 400 versts away; for shipping goods the Belaya River was used, allowing barge rafting only once a year, during spring high water. At the same time, the plant proved to be in complete neglect. All this placed the new enterprise in very difficult conditions: significant cash outlays were required for equipment, far exceeding initial expectations and at that time greatly burdening the trading house.

During the first twenty years of the company’s existence, the enterprise’s financial results were entirely negative. In some years there were not even sufficient funds to pay interest on loans, etc. In such cases the trading house had to pay for the company out of its own funds. Nevertheless, the trading house did not despair and, setting itself the task of developing this district and not wishing to deprive the numerous population of their earnings, continued to gradually overcome difficulties, develop the business, and increase production. Some relief was brought by the construction of the Samara–Zlatoust railway, which brought the works somewhat closer to the rail line, although even then the distance to the nearest station, Vyazovaya, still amounted to 136 versts of difficult mountain road.

The industrial upswing of 1890 for the first time made it possible for several years to pay a modest dividend, but the crisis that then broke out again made this enterprise unprofitable, operating in especially unfavorable conditions with respect to transport routes. Meanwhile, the development of the business required significant expenditure of money; capital was increased first to 1,750,000 rubles, then to 3,500,000 and to 7,000,000. In addition, the trading house also extended broad credit to the company. The necessity of building a railway became ever clearer, and since all attempts to lay a public broad-gauge line remained unsuccessful, the trading house decided in 1910 to subsidize the company with the necessary amount to build, at its own expense, a 137-verst narrow-gauge line. This construction was associated with exceptional difficulties due to the natural features of the terrain and the absence of compulsory expropriation rights; nevertheless, it was carried out in 1911–1913. In parallel, a plan for extensive reorganization and complete modernization of all the company’s plants in accordance with the requirements of modern technology was developed and implemented.

Confident that with the construction of the railway the operating conditions at the plants would become significantly more favorable and the company would be able to provide shareholders with a dividend, it was decided to double the capital and attract new partners. The trading house had not previously dared to use such a means due to the company’s lack of security and, however difficult and unprofitable at times, had continued to bear the entire burden of financing alone—shares belonged almost exclusively to members of the trading house or their relatives who had received them from former members. Now, from the new capital issue of 2,000,000 rubles, it sold to the Russian Bank for Foreign Trade at a fixed price of 110 for 100 nominal, but then the trading house took no part in stock-exchange operations. After this, the trading house retained company shares with a nominal total of only 4,135,550 rubles.

With the outbreak of hostilities, the re-equipment of the plants was not completed, but despite the difficulties of implementing the planned program, there was no delay, and the company—broadly subsidized by the trading house—managed during the war to complete and put into operation the largest wire-rolling mill in the Urals and a completely newly built, also the largest in the Urals, nail-and-wire factory, whose work was fully used for defense needs.

Foreseeing the need for further broad development of the enterprise, but under the prevailing circumstances not having full confidence that it would be given the opportunity to do so, the trading house—solely in order not to serve as a brake on the development of an enterprise so necessary for the country—decided to find an institution capable of appropriately carrying out the program outlined by the trading house, and found such in the person of the Sormovo and Kolomna works, which needed precisely such an enterprise, secured with raw material.

Despite brilliant prospects and enormous reserves of its own land—over 240,000 desyatinas of forest and ore, indicating the enterprise’s great future—the trading house, for the reasons mentioned, decided to отказаться from participation in the business and sold its shares, at the same time renouncing the dividend for the 1915/16 operating year already completed at the moment of sale. To ease the work of the new owners, the trading house also agreed to reschedule over several years the large debt of the Beloretsk company to the trading house in the amount of about 8,000,000 rubles at a very modest interest—6% per annum.

During the period of revolution and civil war, the Beloretsk works were practically stopped and only resumed operation in 1921. They reached the pre-war level of output by 1925–1926.