Socialist measures in the economy were expressed in the fact that industry and trade were nationalized and placed under the jurisdiction of special central bodies under the leadership of the Supreme Council of the National Economy (VSNKh). Factories and plants lacked raw materials, fuel, and labor. Most skilled workers were employed in various responsible posts, and some moved to the countryside to escape famine.

The remaining workers were bound by an almost military discipline. Each violation was punishable by a fine or even arrest. Because of this, and also because of the food problem, unrest and strikes arose. Small industry was under the authority of the provincial and district councils of the national economy. Output in all branches steadily declined.

The population was reluctant to sell agricultural products. Without exchanging for salt, matches, soap, and the like, nothing could be obtained. In violation of existing laws, private trade was widely and openly practiced, with banknotes accepted only as a last resort. The countless amount of paper issued completely devalued money; all enterprises and government agencies existed at the expense of newly issued banknotes. No credit operations were conducted; the State Bank was abolished.

Railways functioned poorly. Trains ran irregularly, and rolling stock was in deplorable condition. Medical care in cities was insufficient, in the countryside it was almost absent, and there were no medicines. Former privately owned estates lay in neglect, although state farms were organized there. In general, the national economy was ruined, and no improvements were noticeable in anything.

EPO branches took over the distribution of bread and the organization of canteens. Because of difficulties with fuel, interruptions in baking were frequent, and canteens sometimes had to be closed. By that time, the ration-card system had not yet been introduced throughout Crimea, although a food census had already been carried out everywhere. In some places, EPO organized vegetable gardens, having received the necessary equipment from the provincial union. In Yalta and Bakhchisarai, gardens were under EPO administration, and in Simferopol the supply of milk for children was transferred to consumer cooperation.

Of the 15 city EPOs, the strongest was the Simferopol one (organized in November 1920). Its board included the majority of the board members of the workers’ cooperative “Tovarishch” that existed by that time. A supervisory committee was also formed, which began inventorying the goods held by the cooperative. The main task was to create distribution shops. By December 20, 1920, 20 distribution points were ready to open. By February 1, 1921, their number had reached 83. From that time, bread baking, public catering, and product distribution passed to the consumer societies. The Simferopol EPO had 12 bakeries and 38 canteens (more than 15,000 diners were supplied by the EPO). By the end of April there were already 33 bakeries and 91 canteens. From February 1 to May 1, 1921, up to 135,000 poods of bread were baked and distributed, and rations of various products totaling up to 100,000 poods were issued.

In 1921, 29 consumer associations were registered in the Simferopol EPO. The total commodity fund was estimated at 500 million rubles (funds were extremely insufficient). Turnover was also insignificant. Overall, the severe situation by the end of the year forced the EPO board to begin staff cuts (from 800 people as of July 1 to 90). The barter point, the soap-making plant, the shoe workshop, and several canteens were closed.

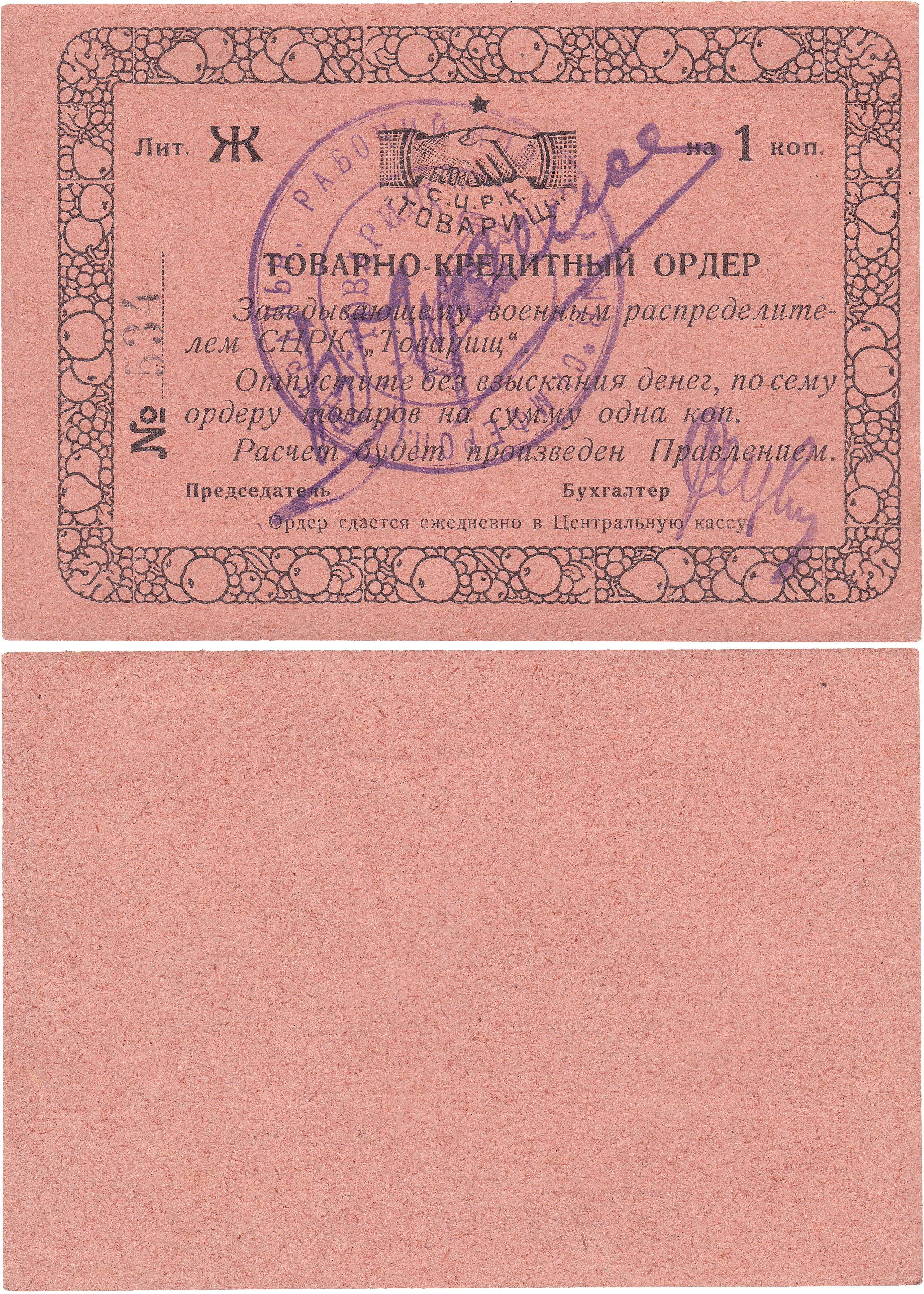

On August 4, 1922, a city workers’ conference decided to merge all cooperatives into a single CRK. Carrying out this consolidation, all groups (two more were added to the first four) pushed the question of the commercial benefit of the merger into the background. As a result, it became necessary to cover the deficits of some cooperatives with the surpluses of others. This, of course, negatively affected the consolidated balance sheet of the merged cooperatives. In the consolidated balance of 40,000 rubles, only 28% consisted of real assets that could serve as working capital. 72% consisted of immobilized, conditional, or negative items (debts owed by various persons and institutions). With such means, from August 1922 the new central workers’ cooperative “Tovarishch” began servicing the city’s population.

In the winter of 1923, the CRK had 3 bakeries producing up to 400 poods of bread per day, a shoemaking workshop producing up to 600 pairs of shoes per month, a collective farm with a cultivated orchard, and a 57-desyatina vegetable garden.

The pricing policy was based on the principle of preserving commodity value, i.e., pricing that assumed the continued fall of the ruble’s exchange rate. However, thanks to minimal organizational and other expenses, the average markup did not exceed 20%, and prices compared to the private market were always 20–30% lower. The net profit resulting from the markup system as of January 1, 1923 amounted to 3.5% of working capital, with all other expenses at 16.7%. Expenses included 23% to the insurance fund, 4% to trade unions, 1% to cultural and educational work, and one-time amounts for the maintenance of an affiliated military unit. Thus, the generally insufficient difference from market prices was offset by these expense items aimed at the overall improvement of the national economy. A more noticeable reduction in prices for the consumer could occur only on the condition of a general economic upturn. Above all, it was necessary to stop the fall of the ruble.

At the all-Crimean conference of workers’ cooperation on June 18, 1923, certain results were summed up. Workers’ cooperatives in Crimea at that time had 17,000 members receiving products at 28 distribution points. The most successful was the Simferopol cooperative “Tovarishch,” which had 5,780 members.

In March 1924, the Simferopol and Sevastopol workers’ cooperatives were admitted as full members of the Centrosoyuz. This made it possible to obtain factory-made goods from producers, bypassing intermediaries. Centrosoyuz established a permanent credit line for the Simferopol CRK “Tovarishch” in the amount of 80,000 rubles in gold. In addition, a railcar of haberdashery and grocery goods was released on credit for 75 days, as well as a railcar of new summer textiles (an arshin of calico cost 30 kopecks). Haberdashery and textile goods were sold to members of the Simferopol CRK with installment payment over two months.

In March 1924, the CRK “Tovarishch” lowered prices in its distribution points for absolutely all goods and, having obtained a credit of 20,000 gold rubles from the State Bank with the help of the Vsekobank?, began to set up meat trading.

In the summer of 1926, the Simferopol CRK “Tovarishch” marked the fourth anniversary of its work. Created from the collapsed local EPO and the failed consumer associations, “Tovarishch” had 102 members and a balance of 40,000 rubles, of which only 28% represented real value. Its own funds were no more than 12,000 rubles; for almost three years even borrowed capital to a significant extent remained in immobilized assets.