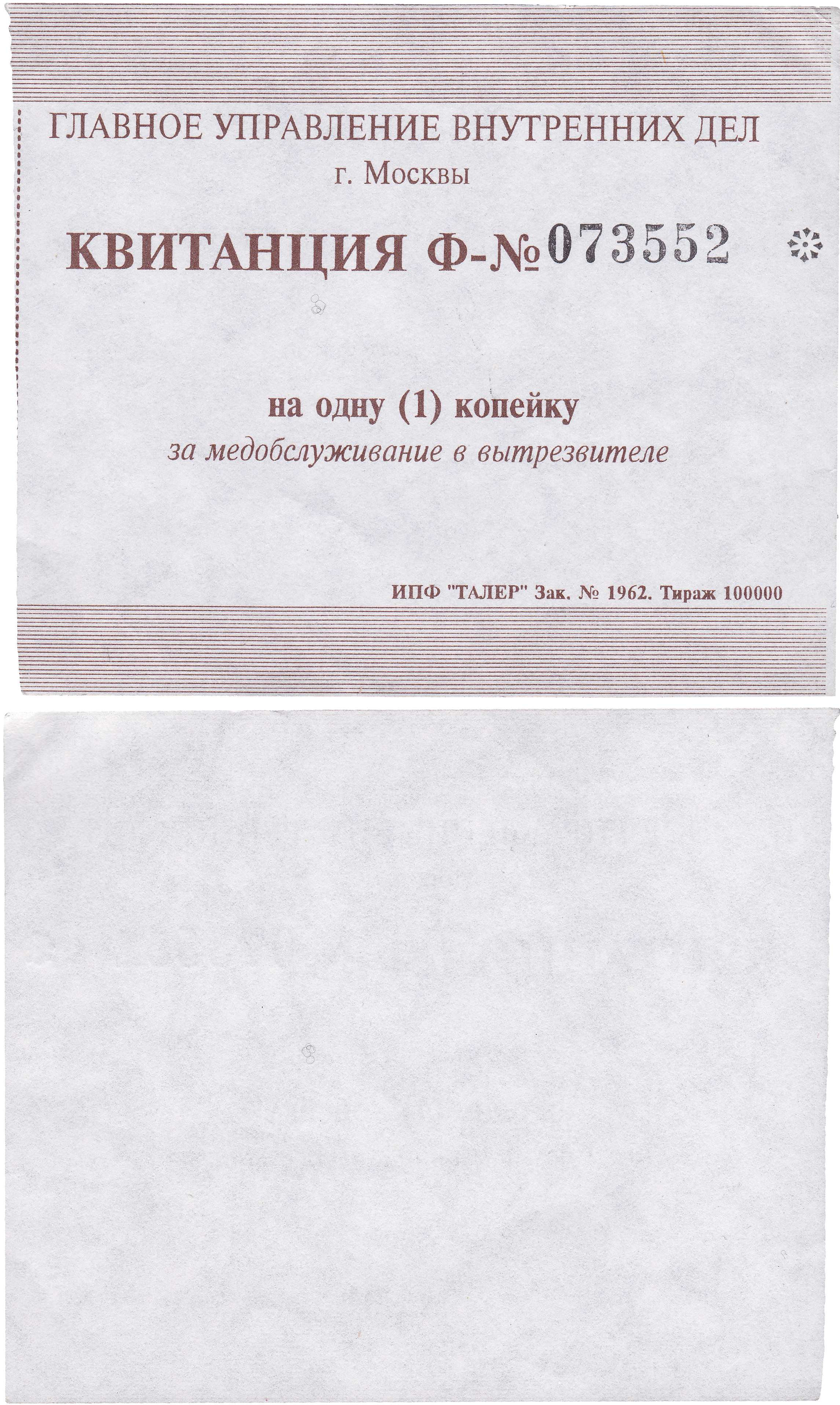

“In 1998–2000 I was a frequent customer at the sobering-up station; in total they hauled me in five times,” recalls programmer Alexander Yulin. “Three of those times I was genuinely dead drunk, and twice they were just filling their quota, so I wasn’t put through any procedures: they kept me for two hours in the ‘shouter’s cell,’ and that was it. The ‘shouter’s cell’ is basically the same as the police ‘monkey house’—a cage for those who aren’t too drunk and aren’t causing trouble. Of course, they still issue you the exact same receipt for ‘services,’ and all the money you had at the moment of detention ends up in the sobering-up staff’s pockets. However much you had, that’s how much they took: once they confiscated 200 rubles from me (which was money in those days), and a friend lost two thousand—back then it was still a tidy sum. But I don’t recall them taking any belongings, although the crowd that ended up there couldn’t have had diamonds or Vertu phones; but they definitely didn’t remove wedding rings.

They treated the drunks politely, but harshly. If you argued or resisted, they could beat you up. Football fans after matches were especially ‘lucky,’ when the cops were all keyed up. If they brought you in wearing a scarf, God forbid you say something out of turn—you’d get hit in the head right away. Otherwise they usually just stripped you down to your underwear; if the passenger was in a really disgusting state—cold shower, then a ward with 6–8 beds, a wool blanket, and lights out. About once an hour they’d drop in to see if there was any commotion, to check whether anyone had vomited. They’d lazily walk along the beds and poke you with the end of a baton—like, are you alive or not? If someone started making noise, there was no medicine—just drag them into the corridor and rough them up. And at seven in the morning—wake-up and goodbye.”

In 2011, the last sobering-up station in Russia was closed.