In the Russian Empire, excise tax stamp bands were issued by the Ministry of Finance and printed at the EZGB.

In 1861–1863, the farming-out system had to be replaced with an excise system, which operated in full force until the introduction of the state sale of spirits, or the drinking monopoly, introduced by the laws of June 8, 1893 and June 6, 1894.

Under the regulations on the state sale of alcoholic drinks, the wholesale and retail sale of spirit, grain wine, and vodka products constitutes the exclusive right of the treasury and is carried out through treasury-owned facilities, warehouses, and wine shops.

All wine offered for sale must be made from rectified spirit, subjected to cold purification through charcoal, and have a strength of not less than 40 degrees.

The sale of wine and spirit from state points of sale is carried out exclusively for take-away in glass containers sealed with the state seal, with a capacity of 1/200 (61.6 ml) of a vedro and above, at prices set annually by the Minister of Finance within norms established by law, and the price of a fraction of a vedro must be proportional to the price of a whole vedro. Vodka products are made at private factories from rectified spirit purchased from the treasury and released for sale under an excise stamp band, the price of which is set at 2 rubles per vedro of products.

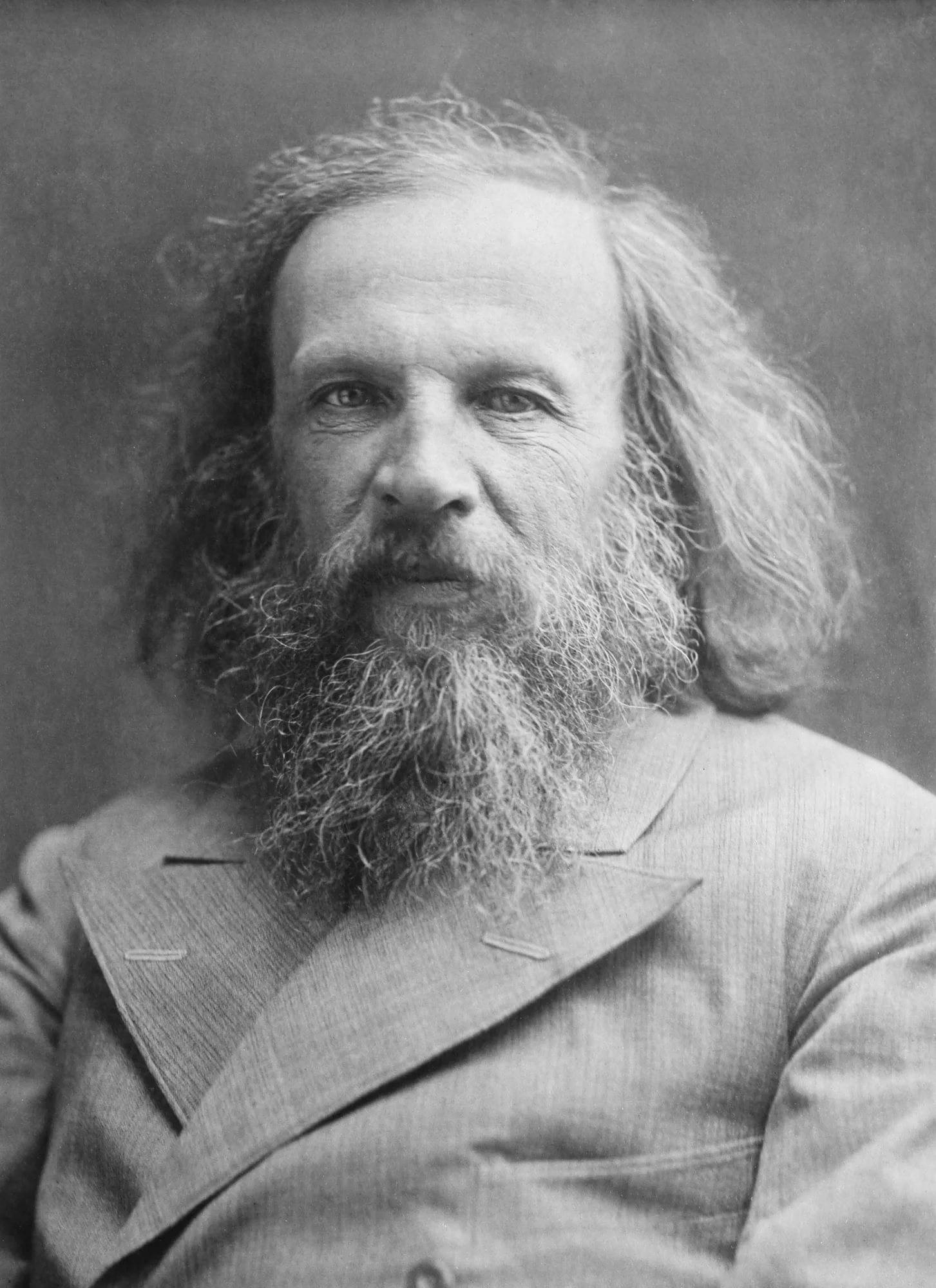

D. I. Mendeleev and many of his colleagues warmly supported the idea of a drinking monopoly.

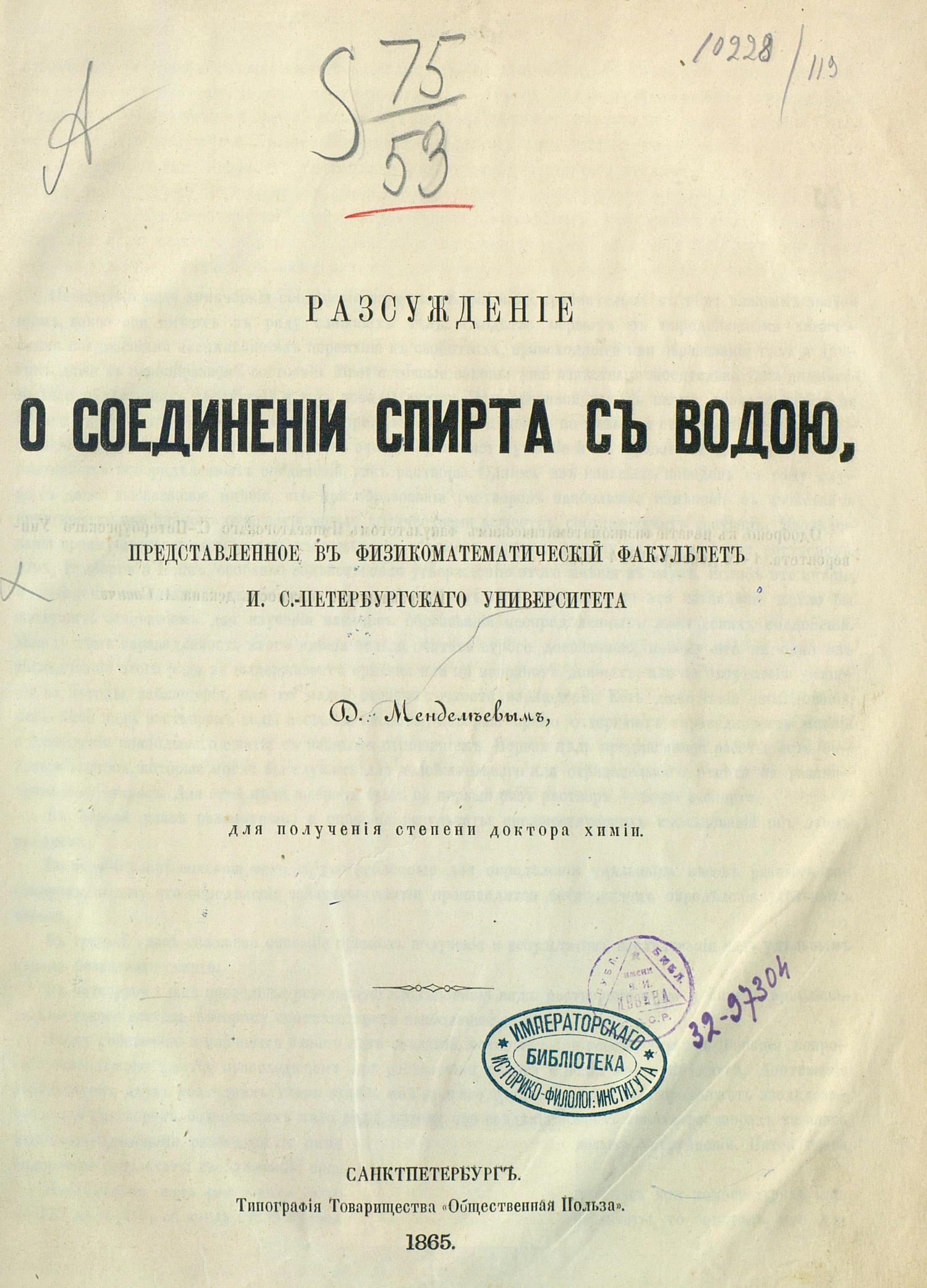

From 1893, a large group of scientists under Mendeleev’s leadership, a number of statesmen sympathetic to Witte, and leading jurists headed by A. F. Koni undertook a comprehensive development of the drinking monopoly. For effective state control over quality, a vodka standard was to exist. It was proposed to use a water-alcohol mixture containing 40 parts by weight of ethyl alcohol, passed through a charcoal filter and containing minimal (stipulated) concentrations of fusel oils. Moreover, the spirit was to be made strictly from rye malt. For vodka production, it was recommended to use spirit at 60–80 degrees, diluting it with water down to vodka strength. The water was to be very soft, not containing many salts and “living,” not boiled. As a result, the reference vodka was described as a clear, colorless liquid with a light characteristic soft спирит aroma and taste. The choice of a 40-degree standard (40 parts by weight) was not accidental. Back in 1864, D. I. Mendeleev defended his doctoral dissertation on the topic “Reasoning on the Combination of Alcohol with Water.”

In this work, he suggested that in a water-alcohol solution, alcohol, depending on concentration, can exist in the form of three hydrates—a molecule of alcohol with one, three, and twelve molecules of water. In a report to the Russian Physical-Chemical Society in 1887, based on his own experiments and data from other researchers, he asserted this viewpoint. These studies formed the basis of the strength standard. If you dilute a 40-degree vodka just a little with water and it instantly becomes watery, try fortifying it slightly with alcohol, and it immediately becomes very strong. These characteristics depend on the viscosity of the alcohol mixture. At an alcohol concentration below 40 degrees, hydrates with 12 water molecules predominate; hence the low viscosity and the sensation of dilution. If the mixture is above 40 degrees, it contains more hydrates with one water molecule; we get high viscosity and a sensation of unpleasant strength and dryness. Only forty parts of alcohol by weight give in solution a balanced mixture of hydrates, the main share of which has three water molecules. Such viscosity of the solution is the only possible one for vodka not to be watery and not to be harsh, but to have ideal drinkability. However, the introduction of 40 degrees was not something new. Even before the drinking monopoly, the market strength of “higher drinks” fluctuated within 38–40 degrees. In addition, in distilling there existed a conventional measure for output: a vedro of spirit at 40 degrees. Therefore, D. I. Mendeleev’s заслуга amounts only to the approval of 40 degrees for monopoly wine and to the theoretical justification of why this was done. The commission headed by D. I. Mendeleev did not develop a vodka standard, but approved its fundamental production scheme, based on centuries of Russian distilling experience. It was created exclusively for state quality control and contained nothing fundamentally new. In 1998, the vodka “Russian Standard” appeared. In the booklet посвященном to this vodka, it is written that “D. I. Mendeleev created not only the periodic table of the elements, but also the standard of high-quality Russian vodka.” In addition, Mendeleev, it turns out, was “a great connoisseur and appreciator of vodka.” The vodka developed by him turned out to be “not only completely safe for health, but even beneficial in moderate quantities.” We believe that the vodka “Russian Standard” is presented as the Russian standard not of the IV drinking monopoly, but of our modern standard of Russian life, where irresponsibility triumphs not only in deeds, but also in words.

In essence, the introduction of a vodka standard in 1895 became a turning point in the modern understanding of Russian vodka in general. Throughout the history of vodka production in Russia up to the end of the 19th century, vodka meant infusions as such—colored, on herbs and berries—and distilled, aromatized, clear ones. If sugar or other sweet substances were added to vodka (an infusion), it was called ratafia; if vodka (an infusion) was distilled several times and a strong (about 60 degrees) drink resulted, it was called yerofeich. In Russia, people tried not to drink a simple aqueous solution of alcohol, whether at 40 parts by weight, or 38, or 56. V. V. Pokhlebkin writes about the 18th–early 19th centuries: “It was considered prestigious to have vodkas with flavorings for every letter of the Russian alphabet, and sometimes two or three vodkas for each letter. They made vodkas such as anise, birch, cherry, pear, melon, blackberry.” In V. I. Dahl’s collection there is a proverb about vodka: “An infusion on St. John’s wort and other harmless herbs.” The old Russian alcohol term “bitter wine” means vodka distilled with slightly bitter herbs (wormwood, birch buds, oak, willow, alder). In Siberia of the 17th–19th centuries they drank anise, wormwood, orange, lemon, St. John’s wort, pepper, fir bitter, cedar, honey, star anise, and many others—infused with Siberian herbs and southern spices that were brought from China with tea caravans through Siberia to Europe. The Kamensky distillery (early 17th century—1850) near Yeniseisk supplied ordinary and sweet vodka with its own spices to Yakutsk, Nerchinsk, Irkutsk, Berezov, Surgut, Narym, Mangazeya, Turukhansk, Krasnoyarsk, Kansk, and Tobolsk. The best vodka in Russia and in Siberia was always what professionals today call “colored vodka”—an infusion—and also clear vodka—a distilled infusion, stronger. Of course, this does not mean that people drank only vodkas enriched with taste or аромат substances. They drank simple vodkas too, made from spirit and water, but these were the cheapest, “unworthy” of a self-respecting person.

The modern concept of Russian vodka as a clear aqueous solution of alcohol with a “characteristic vodka smell and vodka taste” does not have roots going deeper than the IV drinking monopoly (1895). This concept became established among the people due to extensive coverage of all preparatory work carried out by the government in preparation for the drinking reform. Everyone believed that the proposals of the government, scientists, and the Tsar-father would be the best of anything that had existed. And as soon as the reform began to work, it immediately became obvious that one should consume an aqueous solution of alcohol without any additional additives, that this was the real Russian vodka. In confirmation of this, after 1895 all private firms where the reform had not yet begun shifted their ассортимент toward the monopoly type. This last circumstance also played its role in закреплении the “monopoly” image of Russian vodka among the people. The Soviet authorities supported the standard of a birch-charcoal-passed, repeatedly filtered, but ordinary alcohol solution; Western firms adopted it.

Ethanol is the basis of all alcoholic beverages. The recipes for cider, beer, and wine подразумевают that it forms naturally. This method is suitable only for low-alcohol drinks, because yeast cannot reproduce if the ethyl alcohol content exceeds 13–17% (depending on the strain). But when it comes to strong alcohol, things get far more interesting. The basis of strong drinks is spirit obtained by distillation. It comes in two types: distillation and rectification. Accordingly, spirit is called rectified spirit or distillate depending on its origin. The chemical formula remains unchanged, but the taste differs.