Industrial oil production in Chechnya began in 1893. The Grozny oil district, where almost all Chechen oil was initially concentrated, became—alongside Baku—one of the first oil-producing regions of the Russian Empire, and later of the USSR. Natural oil seepages had been observed here long before the start of industrial development of the first fields. For centuries, local residents used oil for household, medicinal, and military needs. For example, they lubricated cart axles with it, burned it in lamps, and even treated people and livestock. It was extracted in a rudimentary way: simply scooped with a bucket from wells less than two meters deep.

From the second half of the 19th century, active geological exploration of the Grozny oil-bearing district began. The proven reserves of crude seriously impressed industry specialists. Scientists, in turn, set about studying its quality. Among them was D. I. Mendeleev. Incidentally, the outstanding Russian chemist was the first in our country to propose using a pipeline to pump oil and refined products. This idea came to him when he visited one of the oil fields in Baku.

According to the “New Rules on the Operation of Oil Fields,” approved by the tsarist government in 1872, the right to search for and extract oil on unallocated state lands was granted to both Russian and foreign subjects on equal terms. Allowing foreigners access to domestic oil deposits was explained by the fact that the country’s oil infrastructure was extremely underdeveloped and needed skilled specialists and advanced technologies. Thus, these rules enabled foreign firms to participate in the investment and technical support of the Russian oil-producing industry.

At the end of the 19th century, several British companies established themselves in Grozny with capital totaling 11 million rubles. British business gradually began to displace the French banking house “Rothschild Brothers,” which had purchased shares of the Caspian–Black Sea Oil Industrial Society and held a leading position among foreign firms. And at the beginning of the 20th century, oil field development in Chechnya was already being carried out by such well-known firms as Oil, Shell, and even the “Partnership for Oil Production of the Nobel Brothers,” which was among the first in Russia to demonstrate an ability to adopt both foreign technical innovations and promising domestic developments. This firm was the first to use gas and oil engines, and it replaced batch distillation of oil with continuous distillation. In addition, it managed to profit even from oil residues and used them as fuel. Petroleum products were shipped across the Caspian Sea to Astrakhan, from there by river fleet to the Volga-region cities, and then by rail to the regions of Central Russia and to Baltic ports.

The memory of the Nobels has been preserved in Chechen toponymy. Between the villages of Bamut and Dattykh there is a road called Nobel-nek (Nobel Road), in honor of Ludwig Nobel, the brother of the founder of the famous prize, who once traveled along it. In addition, until the First Chechen War, residential cottages built by the British for their employees still remained in the Grozny district. In one settlement of this district, a two-story building still stands, erected on a frame preserved from British constructions. And the tanks they left behind were used by local residents for household needs for a long time.

Until 1917, Russia’s oil industry developed at an accelerated pace. Foreign companies devised more and more new projects to improve the extraction, refining, and transportation of oil and petroleum products. Royal Dutch Shell even planned to build the Grozny–Tuapse oil pipeline. In accordance with this plan, design work was carried out and pipes were even manufactured, but due to political instability and the difficult military situation in the country, they were not delivered from warehouses in The Hague to the North Caucasus.

In the Soviet years, Chechnya still ranked second in the country in oil production after Baku. The advantages of Grozny oil were that most of it was produced by natural flowing (gusher) from upper layers and, by its characteristics, was considered noble—that is, low-sulfur (if the quality had been preserved to this day, it would have carried the Brent grade and would be considered one of the best in the world). It was even used to produce a special export paraffin, from which, by special order, candles were later made for the Vatican.

In the Tashkala oil fields (a suburb of Grozny), the method of spiral directional drilling (turbine drilling) was used for the first time in the USSR. The introduction of advanced technology in oil refining helped increase the yield of light petroleum products for high-octane gasoline, which was of enormous importance for the country’s industry. In 1927–1928, to transport oil to the Black Sea coast, the Grozny–Tuapse oil pipeline was built—a project that Royal Dutch Shell had been unable to implement in the pre-revolutionary period. It became the first major trunk oil pipeline made of medium-diameter pipes, joined using electric arc welding. And in 1935, the 155 km Grozny–Makhachkala pipeline was commissioned. At the time, it became one of the most powerful in Europe.

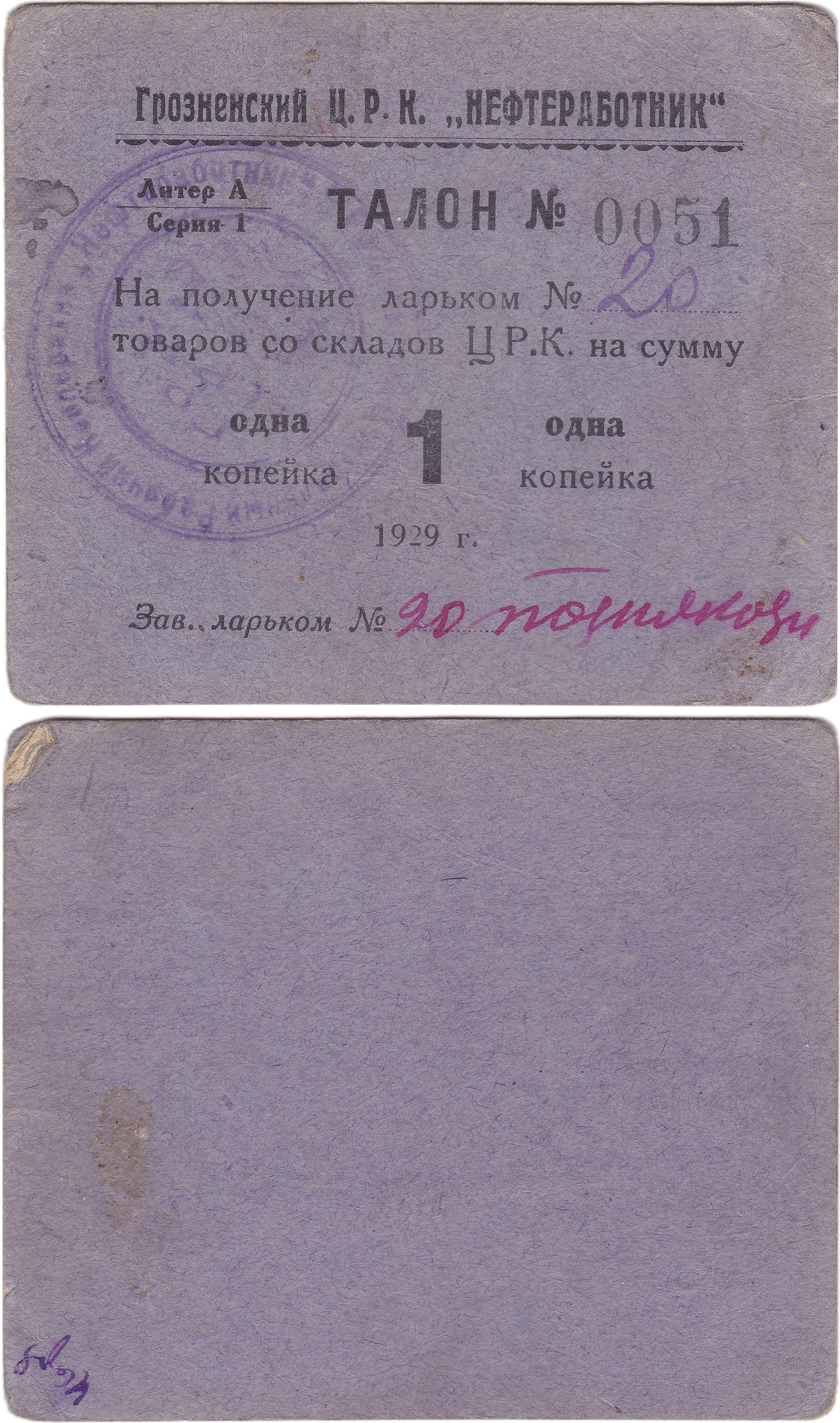

To centralize management of the production process, the “Grozneft Combine” was established, uniting the trusts “Oktyabrneft,” “Starogrozneneft,” “Malgobekneft,” “Grozneftepererabotka,” and “Groznefterazvedka.” In 1920, the Higher Petroleum Technical School was founded in Grozny, which two years later was transformed into the Practical Petroleum Institute, receiving in 1929 the status of a university of all-Union significance. The concentration of scientific and technical thought on such a scale on the periphery in those days was an extremely rare event, but in Grozny’s case it was fully justified. Over time, the institute became the main “forge of personnel” for the USSR oil industry and was the only higher-education institution in the country dedicated exclusively to petroleum.