For the purpose of eliminating kulak households and destroying the kulaks “as a class,” the following legislative acts were issued. On May 21, 1929, the USSR Council of People’s Commissars decree “On the Characteristics of Kulak Households to Which the Labor Code Must Be Applied” defined the features of a kulak household: the systematic use of hired labor; the presence of a mill, an oil press, etc.; the use of a mechanical engine, etc.; the renting out of complex agricultural machines with mechanical engines; the renting out of premises; engaging in trade, usury, посредничество, and the presence of unearned income. In addition, on December 27, 1929, J. V. Stalin, in his speech at a conference of Marxist agrarians, stated: “… from the policy of restricting the exploitative tendencies of the kulaks we have moved to the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class.”

On January 30, 1930, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) issued the resolution “On Measures for the Elimination of Kulak Households in Areas of Comprehensive Collectivization,” which set out a number of measures in these areas: to confiscate from kulaks the means of production, livestock, farm and residential buildings, processing enterprises, fodder and seed reserves (i.e., to dispossess them); with regard to kulaks, who were for the first time divided into three categories: for the first category (counterrevolutionary kulak activists, organizers of terrorist acts and uprisings) — to liquidate immediately by imprisonment in concentration camps, even with the application of the highest measure of repression; for the second category (the remaining elements of the kulak activists, the richest kulaks and semi-landlords) — to exile to remote areas of the USSR or, within the region, to its remote districts; for the third category (the remaining kulaks) — to resettle within the district “on new plots allocated to them outside the collective-farm holdings.”

On February 1, 1930, the decree of the USSR Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars “On Measures to Strengthen the Socialist Reconstruction of Agriculture in Areas of Comprehensive Collectivization and on the Struggle Against Kulaks” was issued; it abolished the right to lease land and the right to use hired labor in individual peasant farms (with certain limitations); it granted regional (oblast) executive committees and the governments of the republics the right to apply “all necessary measures of struggle against kulaks up to the complete confiscation of kulak property and their eviction.”

Order of the USSR OGPU No. 44/21 of February 2, 1930, “On Measures for the Elimination of Kulaks as a Class,” provided for the immediate liquidation of the “counterrevolutionary kulak activists” (the first category of kulaks) and the mass eviction of the richest kulaks and their families to remote northern regions of the USSR and the confiscation of their property (the second category of kulaks).

On February 4, 1930, a secret instruction of the USSR Central Executive Committee “On the Confiscation of Property, Eviction, and Resettlement of Kulaks” was issued; it determined the procedure for evicting kulaks of the first and second categories, including members of their families, and for resettling kulaks of the third category within the district. Settlements within the district were permitted only as small hamlets, to be managed by special committees or authorized representatives appointed by district executive committees and approved by okrug executive committees. Subject to confiscation were the means of production, livestock, farm and residential buildings, trading and industrial enterprises, stocks of food, fodder, and seeds, surplus household property, cash, savings books, and government loan bonds. The dispossessed were left only the most essential household items, the simplest means of production, and a minimal sum of money (500 rubles per family).

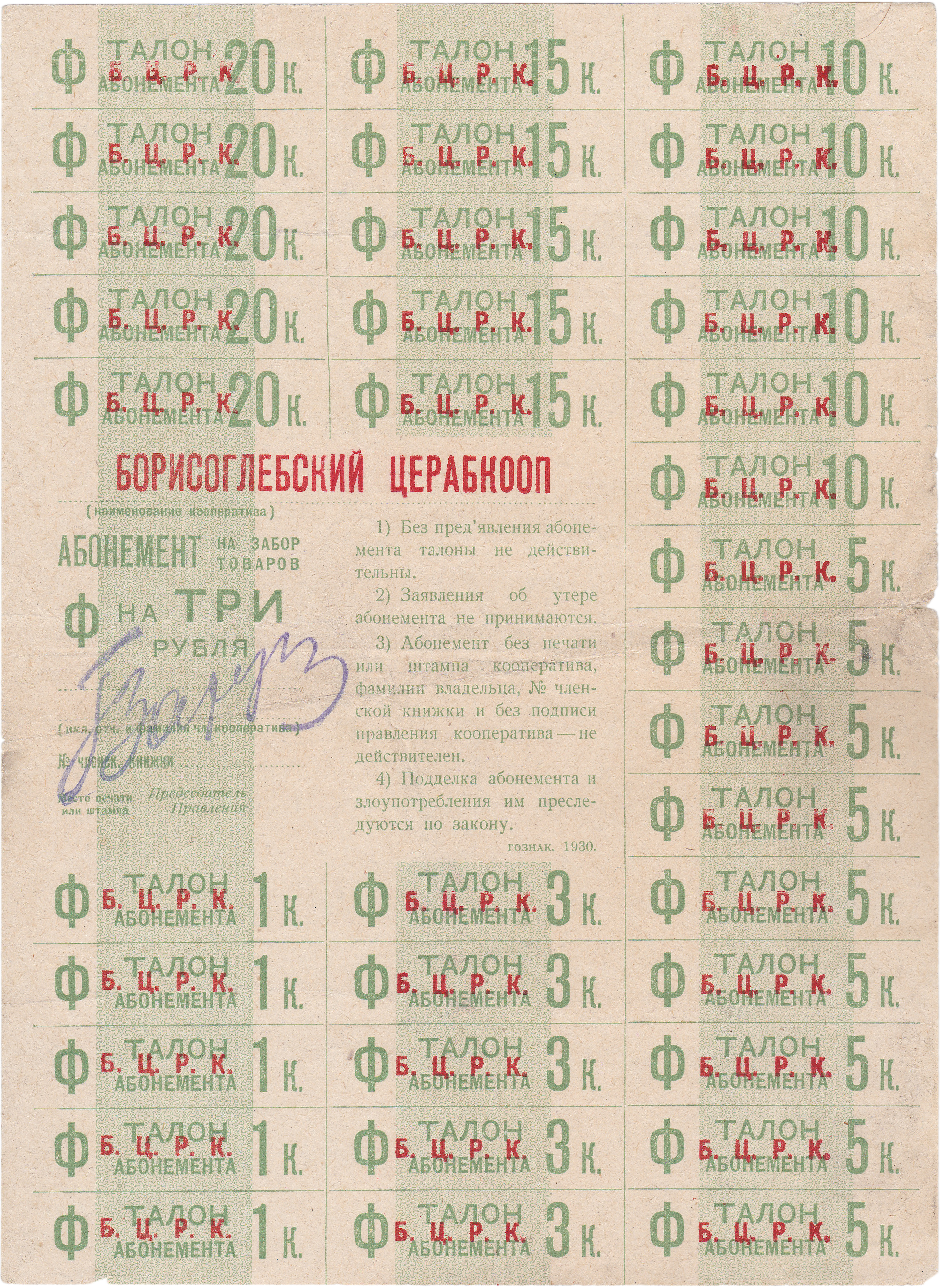

In accordance with the issued directives, the processes of collectivization and dispossession also began to unfold actively in the Borisoglebsky District.

From December 1, 1930, to May 19, 1931, 118 collective farms were formed in the district, uniting 3,279 households, including 392 farm-laborer households, 1,060 poor-peasant households, 1,604 middle-peasant households, and 223 “hard-assignment” households. During this period, 32 households were excluded from collective farms, and 3 households left for seasonal work away from home.

At the general meeting of citizens of the Borisoglebsky settlements on January 4, 1930, it was resolved: “in response to kulak resistance to collective-farm construction… we respond with mass entry into the collective farm,” and “all kulaks and disenfranchised persons who offer active resistance to the cause of collectivization… to ask the OGPU bodies for their immediate eviction beyond the district.”

At the Plenum of the Borisoglebsky District Executive Committee (RIK) on January 9, 1930, under the plan of comprehensive collectivization of the district, a decision was adopted to begin the urgent liquidation and isolation of the kulak-prosperous part of the village, not to admit kulaks into collective farms, “within a week… to begin dispossession,” and to ensure the preservation in kulak households of buildings, equipment, and livestock (not allowing property to be sold off) for its further use in collective farms.

On January 18, 1930, at a meeting of the Presidium of the Borisoglebsky RIK, a report on tasks and further work on collectivization noted: “the masses… raise the question of eliminating the kulak as a class… some are afraid to fight the kulak and in a number of places follow the kulak and treat him conciliatorily… There are people who sympathize and cry together with the kulak, as if what will he do… they have become accustomed to bowing to the kulak, taking off their caps before him — our direct task consists in turning our face to the kulak now in order to wipe him out… The most important thing in the struggle against the kulak is the mobilization of the poor and the middle peasant against the kulak, for the struggle against them… Where to put the kulak. Kulak nests must not be created — go wherever you like, to all four winds, farther away from people. Let them look for a place themselves, and we will say whether it is allowed or not. Some we will leave in such a way that he can only work honestly and usefully; we will force him to live in conditions in which the poor and farm laborers lived…”.

At meetings of the poor-peasant and farm-laborer population, slogans were heard: “Carry out the struggle against the kulak 100% decisively, destroying him as a class; dispossess them and transfer the property to the collective farms,” “break kulak resistance that hinders collective-farm construction,” “immediately take measures against the kulak up to exiling them from the territory of collective farms and confiscating live and dead inventory,” etc.

At a meeting of workers on agricultural collectivization at the Borisoglebsky RIK on January 23, 1930, two approaches used in compiling property inventories of citizens were voiced: “for kulaks everything was inventoried down to the last thread, and for others — the means of production.”

Those subject to dispossession included such categories of citizens as former landlords, traders who used hired labor before the revolution and after it, owners of factories, plants, oil presses, mills, inns, etc., from the very largest to the very smallest, former gendarmes, and clergy.

Moreover, repression affected not only specific representatives of the above categories but also all members of their families; children were held responsible for their parents — they too were deprived of rights, dispossessed, and exiled.

A resident of one of the settlements of the Voshchazhnikovsky Village Council of the Borisoglebsky District, while a student of the agronomy faculty of the Ivanovo-Voznesensk Polytechnic Institute named after M. V. Frunze, was deprived of the opportunity to continue his studies because information reached the institute leadership that he was the son of a dispossessed and exiled kulak.27

The “new” authorities had no question where to get funds to implement their plans; the method was simple: take them from the kulaks. Thus, at a meeting of the board of the collective farm “New Shoots” on January 27, 1930, they spoke about the need to organize poultry and pig farming, and a dairy operation as profitable branches. But how to do it? “Seize kulak buildings with all equipment, land, livestock, and the rest.”28 At the general meeting of the collective farm “Red Shock Worker” of the Neverkovsky Village Council, it was decided to ask the district executive committee “to take from the disenfranchised… household items such as chairs, mirrors, and surplus clothing for organizing a summer nursery in the settlement.”29 A resident of the village of Kushnikovo of the Kondakovsky Village Council (while in military service) wrote in a letter to the chairman of the village council: “I think in my village… to organize a collective farm… in our village there are kulaks… I am afraid that they will not sell anything and… I ask to take everything they have under account… they have two winnowing machines which will be needed in the collective farm… and you, Comrade Chairman, must carry this measure of Soviet power into life… and then it will be easier for me to organize a collective farm… I also ask to take measures that in the village of Kushnikovo… there is a peasant committee and its chairman… who at present is also… a church secretary and… has a brick factory; I also ask to investigate this fact.”

Such denunciations were welcomed when identifying kulaks. As noted at one of the meetings of the Borisoglebsky RIK, “the liquidation of the kulak as a class can be carried out by all measures required by necessity.”

Often, middle peasants suffered along with kulaks. Thus, in the Vysokovsky Village Council, citizens of the villages of Trufantsevo and Aleksino were dispossessed by mistake (true, later the decision on dispossession was отменено, and the confiscated property was returned to the owner, but this was far from always the case).

Often the concept of “kulak” was extended not only to “rural exploiters,” prosperous peasants, but also to those who tried to express even the slightest protest against the policy of collectivization, who did not want or did not dare to join a collective farm.

Personal hostility and slander could decide the fate of entire families. Of interest is the letter-appeal of Nadya Ptitsyna, 12 years old, who lived in the Borisoglebskaya settlement, to J. V. Stalin, in which she wrote: “… my brother and I, until the 14th anniversary of the October Revolution, did not know that father… would be called a kulak… My father organized a collective farm… We handed in everything…: a horse, a cow, a heifer, two calves, and all the agricultural implements we had… and one cow and one sheep remained in our household… And on the second of November of this [1931] year we were given a firm assignment to сдавать for meat a heifer and a sheep, but everything of ours is in the collective farm. And on 3/XI they convened a general meeting and threw us out of the collective farm, and immediately inventoried our property, inventoried everything, and four poods of flour, but our хлеб is collectivized… My brother and I were at the meeting and saw that they voted incorrectly; in the ‘presidium’ everyone whispered… ‘it was for us’ 14 votes against 11 people, and they whispered and said the opposite… They began asking who among the poor had worked for father; nobody said anything… a board member said I worked, and his mother says, ‘why are you lying’… father never traded… outsiders did not work for us either… why earlier, before the collective farm, we were not considered kulaks, and is it right that whoever kept his livestock is a kulak? … Why, because we had two cows and a horse, they began to consider us kulaks, while the poor also have two cows and a horse and do not pay taxes and they are poor… among some kulaks they did not even inventory property… and when they inventoried ours, the chairman… crawled under the bed and kept saying ‘so it’s been cleaned out,’ he doesn’t believe that we have very little. And I go to other girls and see… they live much better than we do… and they hated father… he insisted… that whoever sold a cow before joining the collective farm… the money was paid into the collective farm… Papa went to ask for a resolution… the chairman told him… they will not give any certificates… Yet one must go around not knowing why they want to dispossess us…”.

Collective farmer Titov Sergei Vasilievich, a resident of the Borisoglebsky settlements, “in a heated moment of work in the collective-farm wheelwright shop quit work demanding a high rate, knowing they would give it, and that as a specialist they would not let him go; he did not work for three days.” At a meeting of the poor group it was decided: “son of a trader, traded himself, engaged in profiteering in the collective farm and carried out anti-collective-farm work — dispossess.” However, as Sergei Vasilievich’s wife wrote in her complaint to the Borisoglebsky RIK: “… upon joining we openly… indicated… his father in prewar times started to trade… They pin profiteering on him… but how could one exist with the provision you know at that time in the collective farm. He was not able to steal… And if we take the time when he asked to raise his pay, the head of the collective farm… he from the twenty-five-thousanders… was the first to raise the issue of increasing his own salary… and it was not the time either… Again, Comrade <…> indicates that unsuitable things were contributed to the collective farm, and good ones were kept… what was kept and what was contributed and in what form is distorted beyond recognition… there is an inventory in the collective farm… they play up some bad harness collar that could not be handed in because it was rags…”. Decisions on dispossession “… are taken fundamentally incorrectly… voting arose partly on the basis of personal scores…, the speech of the poor part of the collective farm is completely disregarded… when discussing the candidacy… indicating motives for dispossession, the poor said: we did not put him forward, they offered him to us… having power, some злоупотребляют it, splashing mud before the masses…”.

Excesses in applying dispossession were acknowledged by those responsible for carrying out this measure of struggle against kulaks. As reported from the Neverkovsky Village Council to the district collectivization штаб: “dispossession in the village council has been carried out 100%; all disenfranchised persons have been dispossessed, deprived of means and tools of production…”. But even the reporter made a reservation: “I only fear that in dispossession we may have overdone it a little.”

According to the USSR Central Executive Committee instruction “On the Confiscation of Property, Eviction, and Resettlement of Kulaks” of February 4, 1930, kulaks of the third category were subject not only to dispossession but also to eviction to special settlements outside the territory of collective-farm holdings within the district.

A similar kulak settlement was also organized in the Borisoglebsky District in 1930. Initially, it was proposed to evict kulaks to the Sborno-Borisovskaya forest tract of the Borisoglebsky District; however, later this decision was revised. In July 1930, work began on arranging a new kulak settlement within the Tarasovsky Village Council (the village of Buikino).

A. M. Denisov was seconded as the settlement’s authorized representative from the Borisoglebsky District Executive Committee.

In July 1930, A. M. Denisov submitted a petition to the Borisoglebsky District Executive Committee asking to “hurry” the forestry enterprise in allocating a cutting area for building the settlement, in order to complete the work of clearing the plot of forest before the onset of winter. The settlement’s authorized representative from the Borisoglebsky District Executive Committee was A. M. Denisov.

In July 1930, A. M. Denisov submitted a petition to the Borisoglebsky District Executive Committee asking to “hurry” the forestry enterprise in allocating a cutting area for building the settlement, in order to complete the work of clearing the plot of forest before the onset of winter.

On August 2, 1930, at a secret meeting of the Presidium of the Borisoglebsky District Executive Committee, a decision was adopted to поручить the head of the district administrative department (RAO), the secretariat of the district executive committee, and the district land department (RZO) to compile an accurate list of persons subject to eviction to the kulak settlement; for the RZO to draw up and approve a plan-project of the settlement; for the authorized representative A. M. Denisov to ensure the development of plots for implementing the plan of autumn-spring sowing; for the RZO and the collective-farm section to allocate agricultural implements and draft power; for the RZO and the Borisoglebsky forestry enterprise, within five days, to allocate a logging area for building the settlement; and to set the remuneration of the authorized representative of the settlement at 75 rubles per month.

According to the production plan developed for the kulak settlement for the autumn agricultural campaign from August 1 to November 1, 1930, the settlement’s area was 450 hectares, of which up to 10 hectares were чистым hay meadow, about 100 hectares were shrubs with mowing, about 250 hectares were sparse forest with small mowing areas, and about 100 hectares were dense forest. In the center of the settlement, on a meadow of 5 hectares, it was planned to set up a homestead: the construction of a common residential house for 200 people, a temporary livestock yard for 5 horses and 10 cows, size 25*8 m, and for small livestock — size 10*12 m; for keeping livestock in winter, a silage pit was to be dug for fodder reserves. By August 15, for the needs of the settlement it was decided to seize from the property of kulak households “live” and “dead” inventory and draft livestock: 2 plows, 2 harrows, 2 sets of harness, 2 sets of carts, 2 horses. It was also intended to buy 10 cows, 1 bull, 5 pigs, 1 boar, 30 sheep, and 1 ram. For field sowing and feeding the settlement’s residents, it was planned to use winter and spring crops from the fund of settlement товариществ, which received crops from collapsed collective farms.

Citizens deprived of voting rights and dispossessed were brought in for work to organize the kulak settlement. According to the list of dispossessed households of the Borisoglebsky District, by approximate data, 61 families, 319 people (able-bodied and not), were subject to eviction to kulak settlements within the Tarasovsky Village Council; of these, 1 family had not been deprived of rights, and about 37 people were later restored in their rights. These were citizens of the settlements of the Selishchensky, Voshchazhnikovsky, Bereznikovsky, Kondakovsky, Neverkovsky, Pokrovsky, Vysokovsky, Osipovsky, and Davydovsky village councils. Among them, 13 families were dispossessed under Category II and 47 families under Category III. In total, 75 able-bodied persons were sent to the work. Non-working family members were to arrive at the settlement immediately after the residential house was built.

Payment for timber harvesting carried out by kulaks on the territory of the kulak settlement was proposed to be made to the Borisoglebsky forestry enterprise according to established rates, and the received funds transferred to the disposal of the authorized representative. All revenues were to be concentrated in the monetary fund of the kulak settlement.

In accordance with the decision of the Okrug Executive Committee, persons who maliciously failed to fulfill or evaded performing work in the kulak settlement were to be brought to trial. Permission to leave or depart as a dependent was to be granted only in cases of clear old age, disability, and inability to be used for work in the kulak settlement.

Public catering in the settlement was planned to be organized from kulak rye crops of 1929. In those settlements where there were no collective farms, the harvest was to be gathered; kulak families and authorities were to be given the right to record the gathered harvest and form from it a fund for issuing the labor norm of bread to the kulak settlement. All other food products the settlement population was to obtain independently.

All types of work in the kulak settlement were to be performed jointly, and all products were to go into common use of the population. All branches of the economy were socialized.

According to archival documents for 1930, there was one kulak settlement on the territory of the Borisoglebsky District; it had no name, and it was not possible to determine for what period it existed.

On January 7, 1933, J. V. Stalin, in his report at the joint plenum of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), announced the completion of comprehensive collectivization in the main regions of the USSR, and also noted that “in carrying out the policy of eliminating the kulaks as a class and uprooting kulak nests, the Party could not stop halfway — it had to carry this matter through to the end.”56 On May 8, 1933, a directive-instruction of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the USSR Council of People’s Commissars was issued, “On Ending Mass Evictions of Peasants, Streamlining Arrests, and Relieving Places of Confinement.”57 In 1933–1935, a gradual restoration of rights for “disenfranchised persons” and the dispossessed began; however, this did not at all mean an end to repressive measures against “kulaks.” In the words of J. V. Stalin: “… now the task is to strengthen the collective farms organizationally, to knock out wrecking elements from there, to select real, proven… cadres…,” “… we have achieved that we knocked out, to the very end, the last remnants of hostile classes from their production positions, smashed the kulaks, and prepared the ground for their уничтожение…. But that is not enough. The task is to knock these бывшие people out of our own enterprises and institutions and finally render them harmless…”.