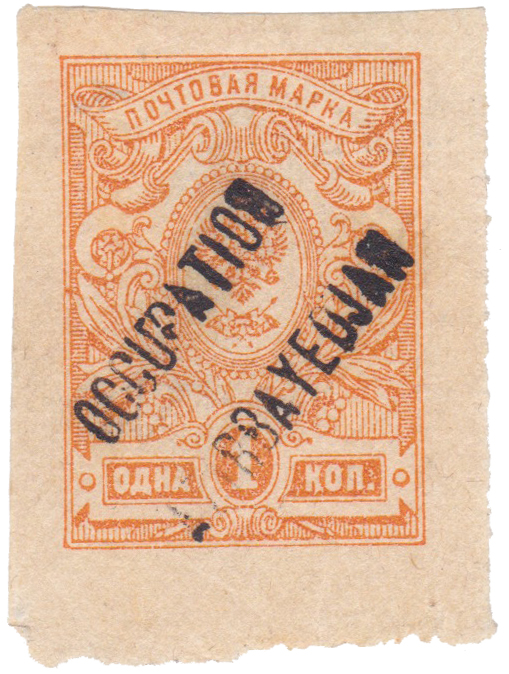

In 1918, a fantastical, speculative issue of stamps of the British occupation administration in Azerbaijan was produced. On stamps of the Russian Empire, an oblique two-line black overprint “OCCUPATION/AZIRBAYEDJAN” was applied. These stamps were allegedly made for May 10, 1917, and are known with forged cancellations dated 10.5.1917 and 19.10.1917; they are also known used on falsified envelopes. The overprints were produced in Paris and in Italy. Many forgeries have fake impressions of guarantee handstamps on the reverse.

There is a version that the overprints were made by the Musavat government at the request of the “Iver” catalogue, but it is вполне possible that emigrants from Russia also took part in this not entirely honorable affair.

After the signing of the Mudros Armistice in 1918, Turkey withdrew its troops from Transcaucasia. And already on November 17, a British detachment under the command of General W. Thomson arrived in Baku from Enzeli.

Even before the allied detachment arrived in Baku, General Thomson demanded that all Azerbaijani units stationed there be removed from the city. In the declarations he signed on November 17 and November 19, the population of Baku was informed that the city, together with the oil-producing districts, would be occupied by British troops.

It is clear that the British were primarily concerned with maintaining order at the Baku oil fields, from which they immediately began pumping oil. Martial law was introduced in the city; the carrying of weapons was prohibited, as were meetings and strikes. To monitor compliance with all these requirements, a police commissariat of the allied powers was established in the territory within a radius of eight versts from the center of Baku, headed by Colonel F. Cockerell.

The British settled into the new place without any restraint. In particular, to house soldiers and officers, the command allocated almost all buildings of educational institutions in Baku, without coordinating this with the local authorities, and the demand of the Baku mayor to pay rent for the occupied premises was simply ignored.

The British also engaged in the de facto requisition of petroleum products, for which the Azerbaijani government did not receive a single kopek, since the British command first secured duty-free export for itself and then refused to pay, citing huge tsarist debts. The government of Azerbaijan was unilaterally notified of the British refusal to pay excise duty.

The British also easily solved the problem of exporting oil and other valuables. In May 1919, the Azerbaijani government was forced to officially acknowledge its subordinate position, confirming in documents the rights of the occupation authorities to the free export of any goods from the territory of the republic. “To let goods for the needs of the British army pass without separate export permits and without collecting duties on them, provided there are certificates from the British authorities accompanying the cargo,” the government decree stated. Azerbaijan, forced to hand over a significant part of its petroleum products to meet the needs of the foreign contingent, in fact found itself in the position of a tributary.

In June 1919, the British command demanded that the government of Azerbaijan allocate to them daily two military trains and one oil train for transporting the oil requisitioned in the republic and for the unhindered movement of servicemen. British officers and soldiers regularly used these exclusive and unprecedented rights in the spring and summer of 1919, practically until their withdrawal from hospitable Azerbaijan. This allowed the British side to minimize transportation costs for the free petroleum products, which ultimately significantly reduced the overall costs of Great Britain for maintaining its military contingent in Transcaucasia. In total, for the transport of various cargoes, the British command owed the Azerbaijani government more than 39 million rubles. In addition, the British took control of the Caspian Sea ports and all vessels located there, which clearly hindered the restoration of full-fledged trade relations in the republic. To manage the fleet, an English Directorate of Sea Transport on the Caspian Sea was created, to which all port fees were now to be transferred.

The Azerbaijani government, faced with the fact of free supply of the British troops with everything necessary, far from only petroleum products, also had to pay the command 35 million rubles monthly for its needs. According to the republic’s Ministry of Finance, as of October 12, 1919, the total debt of the British command amounted to 274,679,690 rubles 88 kopeks. But on November 7 of the same year, the British government refused to accept direct responsibility for this amount, emphasizing that first it was necessary to разобраться in “the responsibility of the Azerbaijani government and the Russian state in relation to this sum, spent under our direction at their joint expense.” The British made it clear that they did not regard Azerbaijan as a state independent of Russia.

It was precisely the uncertainty of Azerbaijan’s international status that served as a cover for the British command for an almost undisguised plunder. Thus, by order of the main British штаб on August 19, 1919, “part of the valuables of the Baku branch of the State Bank, consisting of interest-bearing securities belonging to the State Bank, deposits held for safekeeping, pledged interest-bearing securities, and other valuables,” was taken from Baku to Batum.

In addition to the enormous material damage, the presence of foreign troops and administration in Baku inflicted irreparable damage in the eyes of the population to the authority of the government, incapable of independently managing its own capital. Meanwhile, the gradual decline of discipline in the British units quartered in Baku increasingly led to endless clashes with local residents.

Complaints from residents about the behavior of British soldiers and officers began to arrive more and more often at the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Azerbaijan Republic. One of them wrote in despair that “no one pays attention to our complaints, and the police absolutely do not want to intervene in matters involving the British. The soldiers behave so impudently, disgracefully, and indecently that it is completely impossible for a woman to go out into the street when there is an English soldier there. Drunk, they walk around, stagger, do not let people pass on the sidewalk, grab women, make ambiguous gestures... Is this really a civilized people?”—one complaint said in despair. In the end, popular discontent with the British spilled over on June 13, 1919 into a grand demonstration demanding their withdrawal from Baku.

The British were forced to leave at the end of August, not forgetting to apologize for the inconvenience caused to the population.