Sretenka settlement in the Nizhneingashsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai.

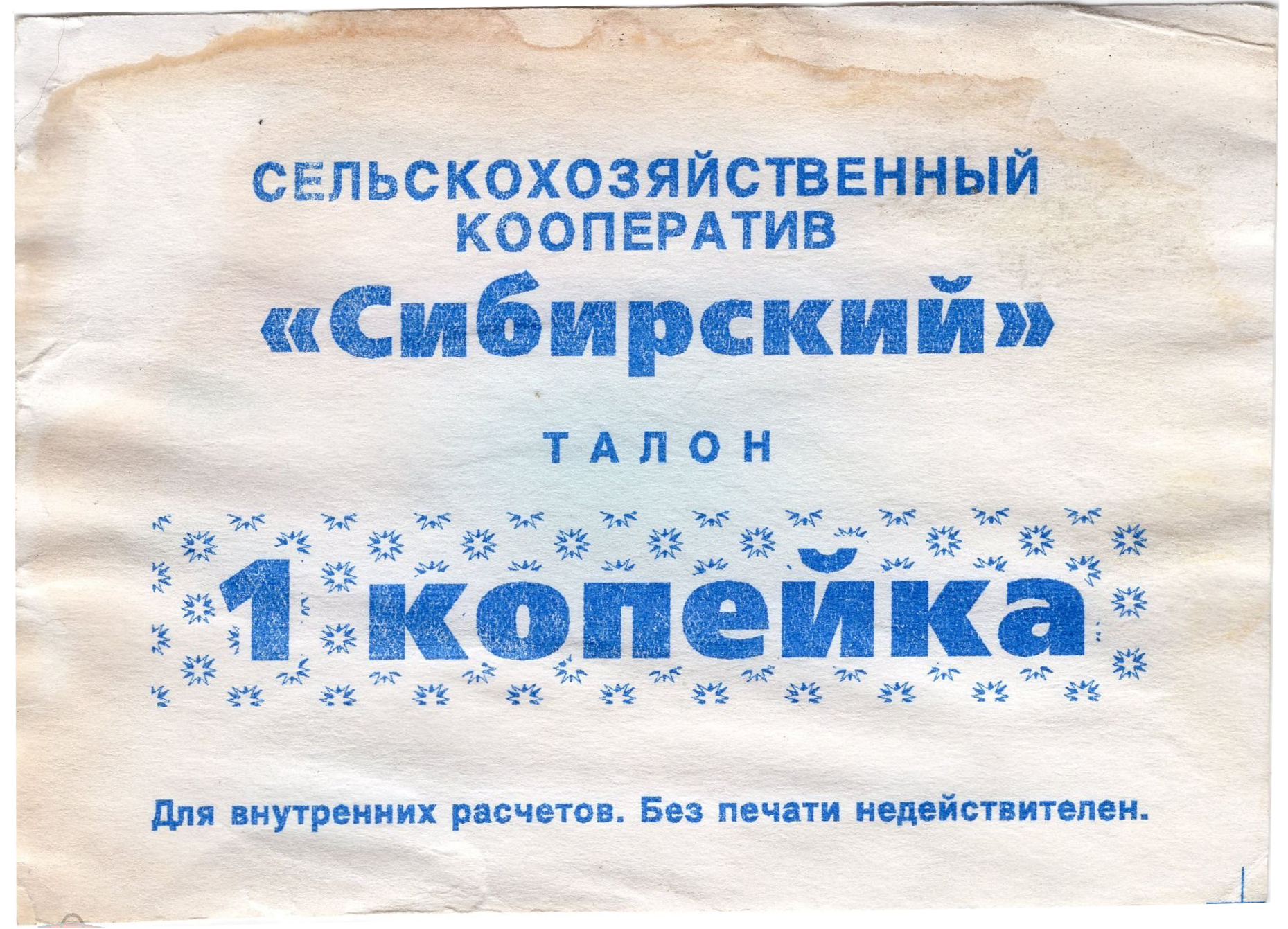

Vouchers of the agricultural cooperative "Sibirsky" may possibly be collectible forgeries.

The Longest Series of Notes. // Collector's Shop 1998. No. 7. P. 3.

Vladimir POLYAKOV

When perestroika began, notaphilists felt at ease: the former dreary, standard requests to search for rarities from different periods of the past had disappeared, because any enterprise had the opportunity to issue rubles and vouchers, checks and warrants, and one only had to keep accumulating information and not refuse offers to acquire new issues. At first, even collectors who had been collecting notes for years easily made mistakes by not buying simple private issues, relying on their easy availability in the future as well. In reality, many of them flashed by like meteors, and finding them now is almost impossible. Today there are few collectors who hurried to study these issues, determine print runs, varieties, and elements of rarity. If some private issues had typographic data about the print run, most had no such data, and sometimes even the year of issue is difficult to establish. And after some time, when forms of ownership began to break down, abuses of these issues appeared, counterfeits emerged, private issues stopped circulating fairly quickly, were withdrawn and destroyed. Nothing remained: neither the notes themselves, nor drawings, nor descriptions. Many of these issues will become rare or even unique, but the true situation will be known only when collectors take up research.

About three years ago I got a series of notes in my hands, primitively designed, with some variety in the artwork, and showing that they had been ordered and produced all at once. We are talking about notes related to agricultural enterprises of the Nizhneingashsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai. Over the course of a year, piece by piece, it was possible to gather some information: they were ordered during one of the zonal meetings along the lines of the collapsing Agroprom and were prepared in one place for everyone who wished to obtain their own currency. However, later events went quite differently. In the district (the meeting was not in the district center) all the prepared signs remained unredeemed, and later some were even burned when the premises were cleared for other needs. Part of the notes was saved from destruction by a former collector who saw preparations for the bonfire begin. The old man supervising the clearing of the premises said that the register listed either 12 or 15 agricultural enterprises, but he did not remember exactly how many and which ones. He also said that the ink color mattered as well. Black was for livestock workers, purple for crop growers, blue for the administration and pensioners, and red for those who either did not live in the kolkhoz or did not work there. There were 17 denominations in total, the same quantities for all; one thousand pieces of each denomination were printed, so there could have been no more than 250 sets, but how many survived is unknown.

In just two small boxes, notes of seven kolkhozes and agricultural cooperatives were found. The denominations were: 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 50 kopeks; 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 rubles (17 denominations). This meant that one complete set contained sixty-eight notes! I have never encountered such a long one-time series again, although I have been collecting for more than 50 years!

It has been noted that there are no more than ten sets of notes of the kolkhoz "Mayak" that bear the seal of the kolkhoz "Svetly put'" (a set with a single ink color: 17 pieces rather than 68, as in other cases). Apparently, when preparing for stamping, they mistakenly used another seal, but did not discard the defective pieces because they needed an even count.

For a number of agricultural enterprises, the names did not correspond to the names of that period. It turned out that the organizations ordering the notes intended to make changes not only to the names but also to the status of the agricultural entities. For instance, "Zavety Lenina" was in fact "Put' Lenina" (Sokolovka village). They wanted to change the signboard of the branch in Kasyanovka village from "Vernogo puti" (board in Pavlovka village) to "Svetly put'". They were going to bring back "Krasny Borets" from the consolidation period, although the village with the same name had already ceased to exist. Transforming the kolkhoz "Estonia" into the cooperative "Sibirsky" would surely have deprived the district of a stable, highly profitable farm with established traditions and hardworking people.

These series, like a mirror, reflect a difficult period in the life of rural districts.

If any collector-notaphilists need these sets (I have several for exchange), write to me; I will definitely reply.

Retired lieutenant colonel of the medical service

Vladimir POLYAKOV,

staff correspondent of "LK".

"30099, Novosibirsk-99,

P.O. Box 147.

The Longest... Forgery // Collector's Shop 1999 No. 5(14) P. 4

Vladimir CHAGIN

This story began about two years ago, when one of the collectors in Novosibirsk started offering notaphilists who collect modern local money substitutes notes of several Siberian farms: the kolkhozes "Mayak", "Zavety Lenina", and others. But since these notes had never been seen anywhere before, and contained no specific information other than the name of the farm and the denomination, they immediately raised doubts about their authenticity.

Nevertheless, as it later turned out, some collectors bought these notes, and eventually they ended up in full in the "Catalog of Modern Cost-Accounting and Private Monetary Issues" (Kyiv, 1998), published by P. Ryabchenko, taking up more than eight pages! In the catalog, the farms that allegedly issued the notes were attributed to the Nizhneingashsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai; settlements on whose territory they were allegedly located were also indicated: Sokolovo, Maksakovo, Verkhny Ingash, Aleksandrove, Kasyanovo, Sretenka. I note at once that some of these villages in fact have different, though similar, names: Sokolovka, Maksakovka, Kasyanovka, Sretenka.

So what are these "for internal settlements" vouchers of seven kolkhozes and agricultural cooperatives?

Their complete set (according to the catalog) totals no less than 493 notes! This huge number came from 17 denominations of each issue (from 1 kopek to 100 rubles), multiplied by four variants of seal colors, plus 17 notes of the kolkhoz "Mayak" bearing the seals of the kolkhoz "Svetly put'". The notes are uniform in type, which, according to the owner, is explained by the fact that they were all "ordered at some meeting" all at once.

But it was not even this incredible number of notes from a remote district of Krasnoyarsk Krai, which suddenly appeared on the collectors' market, that raised suspicion... First, in 1991, the year in which the notes were allegedly issued, there was no particular need to print kopek denominations (1, 2, 3, 5 up to 50 kopeks) (and a year later, because of inflation, kopeks lost any meaning at all). It is no accident that kopek notes in local issues of Krasnoyarsk Krai from that time simply do not exist. For example, the earliest, 1989, cost-accounting checks of the Krasnoyarsk medical preparations plant already had a lowest denomination of 1 ruble.

Second, the very method of producing all these agricultural notes (using a computer, modern duplicating equipment) clearly does not correspond to the time of their supposed issue. Practically all notes of enterprises and farms of Krasnoyarsk Krai at the beginning of the newest period of monetary creativity (1989-1992) were printed in the old, typographic way.

The most amusing part of this whole story is the explanations that were given regarding the names of the farms indicated on the vouchers and their location.

At first it was cautiously claimed that the vouchers were issued in Khakassia. It was pointed out that in Khakassia, which was part of Krasnoyarsk Krai, there were, strangely enough, no kolkhozes at all (see the reference book "Krasnoyarsk Krai. Enterprises and Organizations". Vol. 1, 2. Krasnoyarsk, 1991)!

But then, luckily for the Novosibirsk collector, it was discovered that on the vast territory of Krasnoyarsk Krai there is a Nizhneingashsky District, where there really are kolkhozes "Mayak" and "Pobeda"—in the villages of Verkhny Ingash and Aleksandrovka. Now it was necessary to tie the remaining five kolkhoz-cooperatives to the district—and here all sorts of explanations came into play.

Where, for example, did the agricultural cooperative "Sibirsky" suddenly come from on Nizhneingash land? It turns out it was renamed from the kolkhoz (or perhaps a sovkhoz) "Estonia", though unsuccessfully: this renaming "caused nothing less than national outrage!". (All quotes are from written explanations of that same Novosibirsk collector who distributed the vouchers.) But that is the reality: in the Nizhneingashsky District there was and is no kolkhoz/sovkhoz "Estonia". There is a village called Estonia, which is not the same thing at all. So there was nothing from which to rename the "Sibirsky" cooperative. Another example: "Zavety Lenina" is "Put' Lenina", but since Lenin ended with paralysis, they wanted to change it, and "Svetly put'" seems to sound better than the "correct path", but apparently in the village of Kasyanovka they still have not emerged from poverty... Do any comments to all this even need to be made?!

However, regular readers of "Collector's Shop" can now themselves become acquainted with similar explanations regarding the "Nizhneingash" notes—in the article "The Longest Series" ("LK", No. 7, 1998).. The article is signed with the name of that very collector from Novosibirsk and enriches our knowledge of the "Nizhneingash" notes with new, sometimes dramatic details. It turns out that all these notes were doomed to be burned, but (oh, a miracle!) "part of the notes was saved from destruction by a former collector who saw preparations for the bonfire begin". Another kind person became the source of priceless information about the notes themselves: "The old man supervising the clearing of the premises said that the register listed either 12 or 15 agricultural enterprises". The old man was also initiated into the secret of seal colors: "He also said that the color of the seals mattered. Black was for livestock workers, purple for crop growers, blue for the administration and pensioners, and red for those who did not live or did not work in the kolkhoz...".

Assigning such great significance to each seal color—this seems never to have happened in the entire history of monetary emissions! True, what practical need there was for such a color distinction between livestock workers and, say, crop growers is impossible to guess! The category of "those who do not live or do not work in the kolkhoz" also remains mysterious. One asks: if they do not live in the kolkhoz and do not work there, why stamp special money for them?! In general, the deeper into the Nizhneingash forest, the more firewood, as the saying goes!..

... The article provides exact information regarding all denominations of the "Nizhneingash" vouchers, meticulously counts their number, and gives other details. But at the same time, not a word is said about where and when the "zonal meeting along the lines of Agroprom" took place at which the vouchers were allegedly ordered, or where they were printed ("in one place"). And all the heroes of the voucher-rescue operation also remained unnamed—"a former collector", "an old man"... The secret of these omissions, in my view, is obvious and simple: all precise information (dates, surnames, and so on) is easy to verify, and such a check will expose the makers of the vouchers completely...

So what is the conclusion?

All these so-called kolkhoz vouchers of the Nizhneingashsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai are nothing more than forgeries for collectors, made, apparently, at the same time they began to be offered to notaphilists, i.e., in 1997.

Moreover, to increase their quantity without any significant additional expense, each series was stamped with the same seal in four different colors. The farm names were chosen to be the most common—maybe it would pass... But after collectors to whom the vouchers were offered began to ask questions about the place and time of issue, they were ultimately tied to the Nizhneingashsky District. As we see, not very successfully...

Yes, the "Nizhneingash" vouchers are indeed the longest series of notes—but of fake notes.