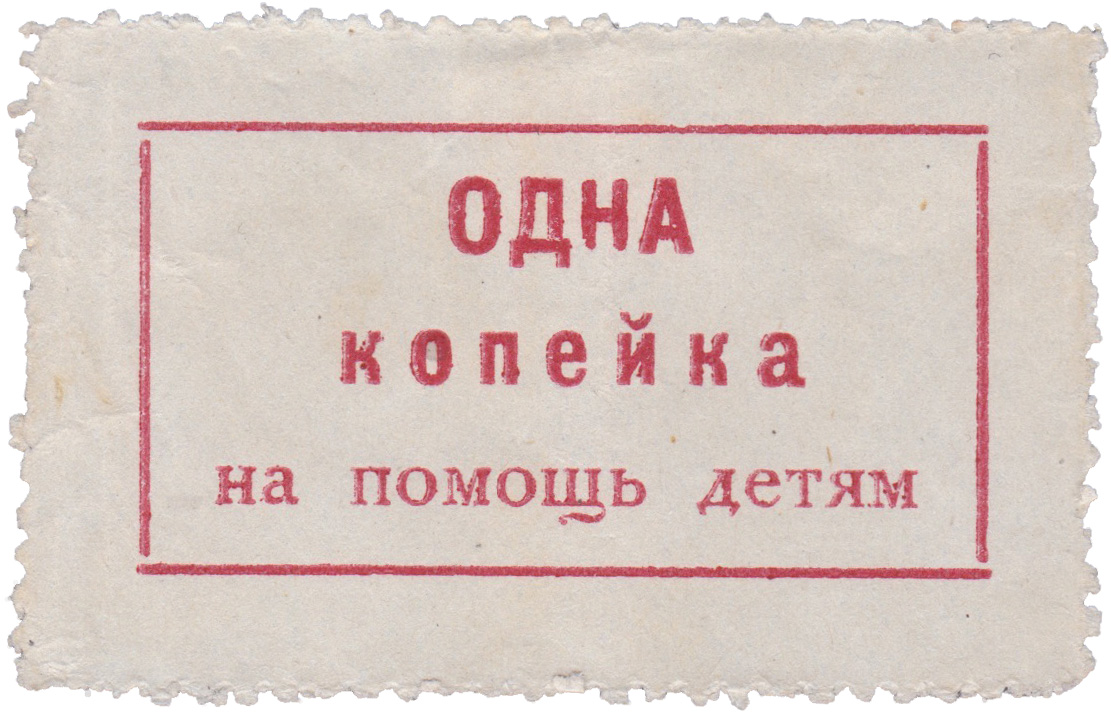

With perforations.

According to some reports, they were used as a mandatory levy and were affixed to wine bottles.

From 1914 to 1921, Russia lost about 16 million people; many families broke up, and mass child homelessness emerged. In 1913, complete orphans made up no more than 25% of homeless children; by 1918, 40–45%, with the majority being children of workers. Children of petty-bourgeois families were more often taken in by relatives or friends of the deceased. The number of children of peasants ruined by the war was increasing.

In 1918–1920, orphanages were administered by the People’s Commissariat of Social Welfare.

At the end of 1917, the People’s Commissariat of State Charity and the People’s Commissariat of Social Welfare were established and were given all authority in the field of public charity. By decrees and regulations of these commissariats, almost all charitable organizations that had operated in Tsarist Russia were abolished, and new Soviet bodies were created in their place: the Board for the Protection of Motherhood and Infancy, the Fund for the Support of Red Army Soldiers’ Children, and others.

The Decree of 17 January 1918 on commissions for minors abolished imprisonment and courts for children of both sexes under 17. From then on, they fell under the jurisdiction of commissions on minors. All court cases involving children, even those already concluded, were subject to review by these commissions. The commissions for minors were under the People’s Commissariat of Public Charity and included representatives of three departments: public charity, education, and justice. The commissions could release minors from punishment or send them to one of the “shelters” of the People’s Commissariat of Public Charity (depending on the nature of the act). Orphanages were under the People’s Commissariat of Social Welfare (children were equated with disabled members of society entitled to full state support). A significant part of them was consolidated into so-called children’s towns in Malakhovka (16 orphanages), Bolshevo, and others. The Moscow children’s reception and sorting facility was housed in the Danilov Monastery.

In February 1919, the Council of People’s Commissars established the State Council for the Protection of Children, chaired by A. V. Lunacharsky. It included representatives of the commissariats of labor, social protection, and food supply. At the same time, the Children’s Rescue League, created in 1918 by public activists, teachers, and cooperators, was active; it used healthcare institutions, former shelters that had belonged to the department of Empress Maria, and created its own labor colonies.

In 1920, orphanages were transferred to the system of public education authorities. By that time, orphans among homeless children exceeded 60 percent. A decree of 4 March 1920 required the People’s Commissariat of Justice to house minors separately from adult criminals and to create special institutions for adolescents. In the 1920s, closed children’s colonies and labor communes were formed (under the NKVD). As an educational measure, minors could be placed in reformatories.

Famine began. Over two years (1920–22), the number of homeless children increased by an order of magnitude. Orphans made up 70–80% of the total, and most of them were of peasant origin (up to 40%). There were more children from well-to-do families among the homeless as well—kulaks, engineers, and nobles. The main ways children obtained food became criminal: theft, robbery, profiteering, prostitution. From 1921, information about orphaned children should be sought in the materials of the Children’s Commission under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.

On 26 January 1924, under the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, a Special Lenin Fund was created to help starving and homeless children. In 1925, there were 200,000 homeless children in the country, 90,000 of whom needed immediate assistance. Orphanages housed 241,000 children, which was 55% of the total number of orphans. “Friends of Children” societies were created in 17 provinces; they had their own clubs, canteens, tea rooms, and shelters. In 1930 these societies received even more authority and also all-union support: on 30 November, under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR, the All-Russian society “Friend of Children” was created.

On 27 January 1921, a special Commission for Improving Children’s Lives was established (the Children’s Commission under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee). It included representatives of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (central trade-union bodies), the people’s commissariats of education and the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate, health, the Central Committee of the Komsomol, the women’s department, and the agitation and propaganda department of the Central Committee of the RCP(b), as well as the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution (Cheka). In the State Archive of the Russian Federation, Record Group 5207 contains materials of the Children’s Commission under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. That same year, a decree was issued on organizing a children’s social inspectorate tasked with combating child homelessness, juvenile delinquency and crime, and protecting children from exploitation and mistreatment. Children were transported under guard to less affected provinces; sent to hospitals and other emerging children’s institutions; actively placed under guardianship with families of “party Soviet workers and candidates,” and even with families of foreign comrades, in particular in Slovakia and Moravia. In Moscow alone in 1920–1921, 24,000 homeless children were settled with families. Some adolescents were sent to Red Army music units. In 1921, 150,000 children from the starving Volga provinces were evacuated through the Children’s Commission to more secure areas; more than 200,000 were taken into care by Red Army units, Cheka подразделения, trade unions, and peasant organizations. In the same year, the Children’s Commission under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee cooperated with the relief fund of the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, as well as with the American Relief Administration (ARA), but at the end of 1921 it was stated that the ARA was being actively used for intelligence and subversive activities, which led to the curtailment of its work in the RSFSR.

Special children’s institutions were created: reception-and-distribution centers (for temporary stays); orphanages; “communes” and children’s “towns.” Orphanages were intended for children up to 12–14 years old. Labor communes accepted adolescents of older ages. Children’s towns were associations of several orphanages, schools, and factory-apprenticeship schools (FZU) with supporting infrastructure and auxiliary facilities. Through 200 reception-and-distribution centers created in 1921, designed to receive 50 to 100 children at a time, more than 540,000 children passed in a year.

In March 1922, an additional oversight body was created: the Children’s Social Inspectorate under the Department for the Legal Protection of Children of Narkompros. It dealt not only with homelessness, but also with protecting minors in families, at workplaces, and in children’s institutions.

On 26 January 1924, under the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, a Special Lenin Fund was created to help starving and homeless children.

In 1925, there were 200,000 homeless children in the country, 90,000 of whom needed immediate assistance. Orphanages housed 241,000 children, which was 55% of the total number of orphans. “Friends of Children” societies were created in 17 provinces; they had their own clubs, canteens, tea rooms, and shelters. In 1930 these societies received even more authority and also all-union support: on 30 November, under the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People’s Commissars of the RSFSR, the All-Russian society “Friend of Children” was created.

A quote from Makarenko’s work: “The homeless children of 1921–1924 have long since disappeared... Our present-day homeless child is not a product of class disintegration... The present-day homeless child is, above all, a child who has lost a family. There are many reasons for this: a freer form of family, the absence of forced cohabitation, a more intense movement of a person in society, a heavier workload for father and mother, a woman’s departure from family narrowness, material and other forms of contradictions.”

From 1918 to 1926, it was impossible to adopt a child. In 1926, the ban on adoption introduced in 1918 was lifted. A campaign began to adopt children and reduce the burden on orphanages. The 1926 RSFSR Code of Laws on Marriage, Family, and Guardianship legalized de facto marriage. Sufficient conditions for its recognition were cohabitation, running a joint household, and joint upbringing of children. The Code gave the court the right to order the removal of children under 14 from their parents and their transfer to guardianship and trusteeship bodies, and it permitted the adoption of minors.