The International Red Aid (MOPR) was a charitable organization established in 1922 by a decision of the 4th Congress of the Comintern as an analogue of the Red Cross. MOPR was a non-party organization and set itself the task of providing legal, moral, and material assistance to imprisoned fighters for the revolution, their families and children, as well as the families of fallen comrades. MOPR brought together broad masses of workers, peasants, and lower-level employees regardless of their party affiliation.

In reality, MOPR was an instrument for popularizing communist ideology worldwide and also served as cover for the activities of Soviet special services. From a propaganda standpoint, however, the idea of creating MOPR was very successful. The theme of rescuing unjustly accused workers from imprisonment seemed extremely noble to the world public, so the number of MOPR members around the world began to grow rapidly from the very first days of the organization’s existence. It is obvious that the “creator” of MOPR, the Soviet Union, had to remain an example for all fraternal communist parties in this matter. Therefore, initially voluntary membership in the organization quickly turned into “voluntary-compulsory” membership. Those who did not join had to follow the example of the “most conscious” workers who had entered the organization, not out of solidarity or humanism, but in order not to attract complaints.

In March 1923, the Central Committee of MOPR declared the Day of the Paris Commune (March 18) its holiday. By 1924, the organization had sections in 19 countries. By 1932, MOPR united 70 national sections with about 14 million people (of whom 9.7 million were in MOPR of the USSR, whose contributions to the fund were the most significant). Until 1936, MOPR, like the NKVD, had the right to issue permits to enter the USSR.

The issue was not so much “terror” against revolutionaries as the fact, which became obvious by the 1920s: the idea of a world revolution was still very far from realization. In order not to finally undermine the trust of the masses in the coming victory of the world proletariat, it was necessary, on the one hand, to promote in every way the thesis of constant “persecution” of revolutionaries abroad, and on the other hand, to form a mechanism of material support for Western communist and other “left” organizations whose activities were aimed at “fanning” the global revolutionary fire.

It is believed that the name for MOPR was придумed by the head of the Polish section of the Comintern communists, Julian Marchlewski. A loyal associate of Rosa Luxemburg and Jan Tyszka, one of the founders of the German Spartacus League (read more about the German Spartacus League in the story “From Trumpeter to Drummer”), and the head of the Revolutionary Committee of Poland, he became the first chairman of the Central Committee of the International Red Aid. The MOPR Executive Committee was headed at the same time by Clara Zetkin, one of the founders of the Communist Party of Germany, who became the leader of the organization after Marchlewski’s death in 1925. Her deputy was a Russian, the prominent scientist Panteleimon Lepeshinsky.

Naturally, the USSR transferred the largest sums of donations “for the prisoners of capital,” the main source of which was voluntary, in some places compulsory, and sometimes outright violent collections of money from the population. And if foreign sections of MOPR collected funds to help their own communists and political prisoners, in the USSR people were urged to “give the last shirt off their back” to help numerous foreign “brothers.” It can be stated with confidence that it was MOPR that laid the foundation for the grim Soviet tradition of aiding fraternal communist parties, and later entire peoples, at the expense of its own citizens.

Over time, MOPR de facto turned from an international aid organization into a mechanism for distributing funds collected in the USSR to support fraternal communist parties.

Over time, MOPR turned into a gigantic “state within a state.” By 1940, that is, over 18 years of work, about 180 million rubles had been collected “for the prisoners of capital”—a simply fabulous sum. But whereas in the first years of MOPR’s existence absolutely all the collected money went to support prisoners, from the second half of the 1920s about one third of the funds began to be kept for the needs of the organization itself, which had grown to incredible proportions. And although assistance to fighters for the revolution in capitalist countries formally remained MOPR’s main goal, in reality the organization engaged not only in that, but also in attempts to create communist cells in countries where the communist movement was known only from newspapers.

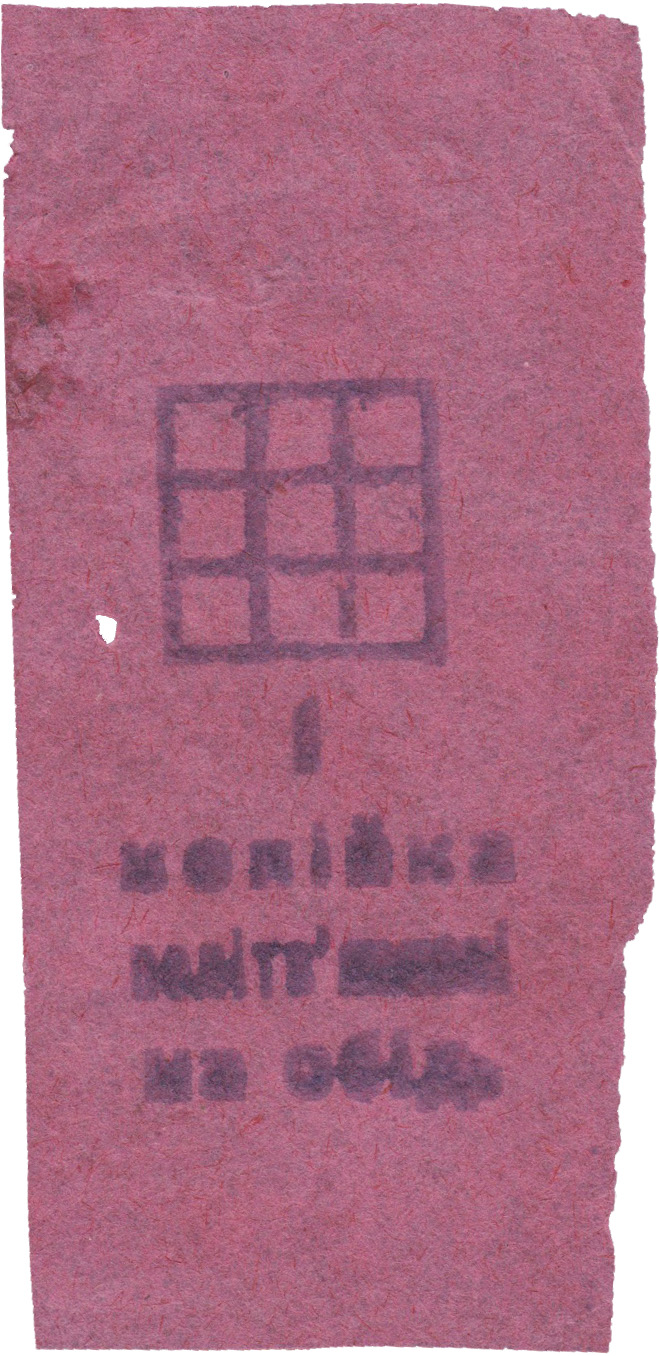

Soviet MOPR members came up with ever new ways to collect as much money as possible from the population for foreign “prisoners of capital.” For these purposes, MOPR of the USSR issued lottery tickets, postage stamps, postcards, held auctions, organized volunteer workdays (subbotniks), and sold charitable magazines from foreign sections. By the way, it was a bundle of exactly such magazines that Comrade Vyazemskaya, the head of the cultural department of the building, insistently urged Professor Preobrazhensky to buy in Mikhail Bulgakov’s famous novel “Heart of a Dog.”

On the international scale it operated until World War II. On April 12, 1948, the Central Committee of the International Red Aid of the USSR decided to dissolve the Soviet section. All property and valuables of MOPR were transferred to the Union of Societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. However, the reason for the liquidation of the organization was not only waning enthusiasm. The dissolution of MOPR was driven by the need to unite all anti-fascist forces. And national and class-based approaches to friendship, as World War II showed, were mortally dangerous. MOPR disbanded quite painlessly, without in any way emphasizing that the world proletarian revolution for which it had been created never took place.