The methods previously used in Russia to keep records of tax collectors—based on a payment book and the complex written reporting inseparably connected with it—proved in practice to be inconvenient, especially in areas with a semi-literate and illiterate population. Settlements in such areas were in most cases made “from memory” and “on trust,” and the payment books often remained unused and were even destroyed. In such a case, the payer, having paid the monetary dues, received no reliable sign confirming the payment of the levies. Confusion often arose in the accounts, and supervision of the collectors’ own activities was hindered.

In view of this, the former justice of the peace mediator of Podolia Governorate, M. A. Skibinsky, proposed introducing for the illiterate a stamp-based system of tax administration that would eliminate arithmetic entries and be understandable to everyone. He justified his proposal by noting that the rural population had long been accustomed to settling with landowners for the use of land by means of so-called “chits,” which had sometimes existed for decades and even centuries. In settlements between payers and the collector, Skibinsky replaced handwritten chits with printed stamps.

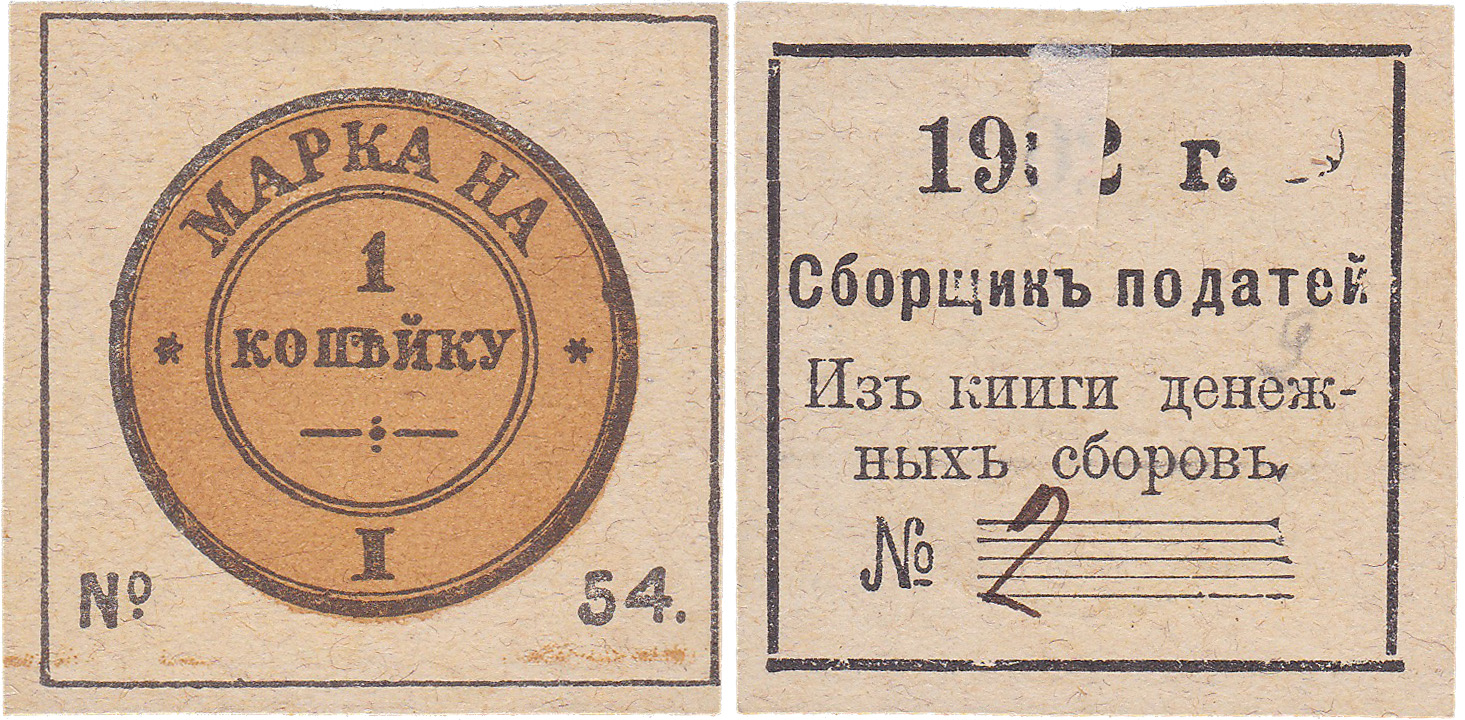

In the design of the stamps, to make them understandable to the illiterate, all features of monetary value long familiar to peasants were combined: stamps depicting coins of less than one ruble were given a round shape, while the rest were quadrangular. The coloring of the stamps matched the color of the monetary token depicted by the stamp: the one-ruble stamp was yellow, the three-ruble stamp green, the five-ruble stamp blue, the ten-ruble stamp red; silver coins were indicated in gray, copper coins in brown. Also, to distinguish the number of rubles and kopecks on the stamps, the corresponding number of small bars was printed.

To control collectors on the one hand and safeguard the interests of payers on the other, each stamp was made personally assigned by indicating on the reverse the number of the household head to whom it belonged. All stamps of one payer were placed on a single sheet intended only for him and secured by separate numbering. Next to the stamps on the same sheet were indicated the payer’s given name, patronymic, and surname, all taxable items belonging to him according to his household list, and the levies due from him. Thus an individualized tax sheet was obtained, on which were grouped all tax demands предъявленные to the payer, all grounds for these demands, documentary tokens (stamps) protecting the payer from repeated collection of the same levies, and all the payer’s personal accounts with the tax collector. The sheets of all payers under a collector’s authority were bound into a cord-bound so-called “control book,” which was kept by the collector.

Tax stamps were used in collecting direct taxes from persons of the tax-paying estate living in rural areas. Initially, as an experiment, they were introduced in certain rural communities of Podolia Governorate (Ukraine), which confirmed the convenience of their use.

In practice, tax stamps began to be used from 1893. They were introduced in 44 uyezds of 21 governorates and in the Turkestan Territory. The benefit of introducing tax stamps was recognized at congresses of tax inspectors of the Turkestan Territory and Olonets Governorate, as well as by a number of provincial and uyezd institutions for peasant affairs and by tax inspectors of many uyezds.