Sosva—until the 20th century it was spelled without the soft sign: Sosva. Sos means “sleeve,” va means “water”; that is, Sosva is “sleeve water,” “sleeve-river.”

After Yermak’s successful campaign in Siberia, interest in the newly acquired lands rose sharply, and the main route from Europe to Siberia up to 1600—until the Verkhoturye road was built—ran along the Vishera and Lozva rivers. Seeking to take control of lands beyond the Urals as well, Russians pushed into the headwaters of the Lozva, Sosva, and Tura rivers. But the local yasak-paying population was not known for being peaceable. Thus, the salt works established by the Verkhoturye people as early as 1600 on the Neglya River were repeatedly targeted for destruction by the Sosva Voguls. And in the spring of 1604 the Lyaly and Tagil Voguls urged the Sosva Voguls to join in a common uprising. Their plans included beating “Russian” people, coming with war to Verkhoturye and attacking the town, burning it, and killing Russian people along the roads and in the fields.

In the “Dictionary of Verkhoturye Uyezd,” published in Perm in 1910, it is said that “the Sosva volost of yasak-paying Voguls, recently abolished by the administration, is a historical term. Before its abolition it consisted of 8 Vogul settlements: Tarakanovsky, Mishina, Malyy Mys, Morozkova, and others. These settlements were located in a checkerboard pattern interspersed with the villages of the Ust-Lyalya volost.”

Mishiny yurts (the village of Mishino, which is part of the settlement of Sosva) have been known since 1718 from the list of newly baptized Voguls of the Tobolsk Spiritual Consistory. The residents of Mishiny yurts, the Voguls, were baptized by Philotheus, Metropolitan of Siberia and Tobolsk, in 1714. The newly baptized Voguls numbered 21 males and 15 females, belonging to the parish of the village of Koshay. In the 1816 census of the yasak-paying Voguls of the Sosva volost, in the village of Mishino there were 5 households, with 54 residents of both sexes.

In May 1880, at the mouth of the taiga river Olta, where it flows into the Sosva River on the lands of the Koshay peasant community, construction began on the Sosva cast-iron plant. The construction started by the von Tal partnership passed to the Kolomna joint-stock company.

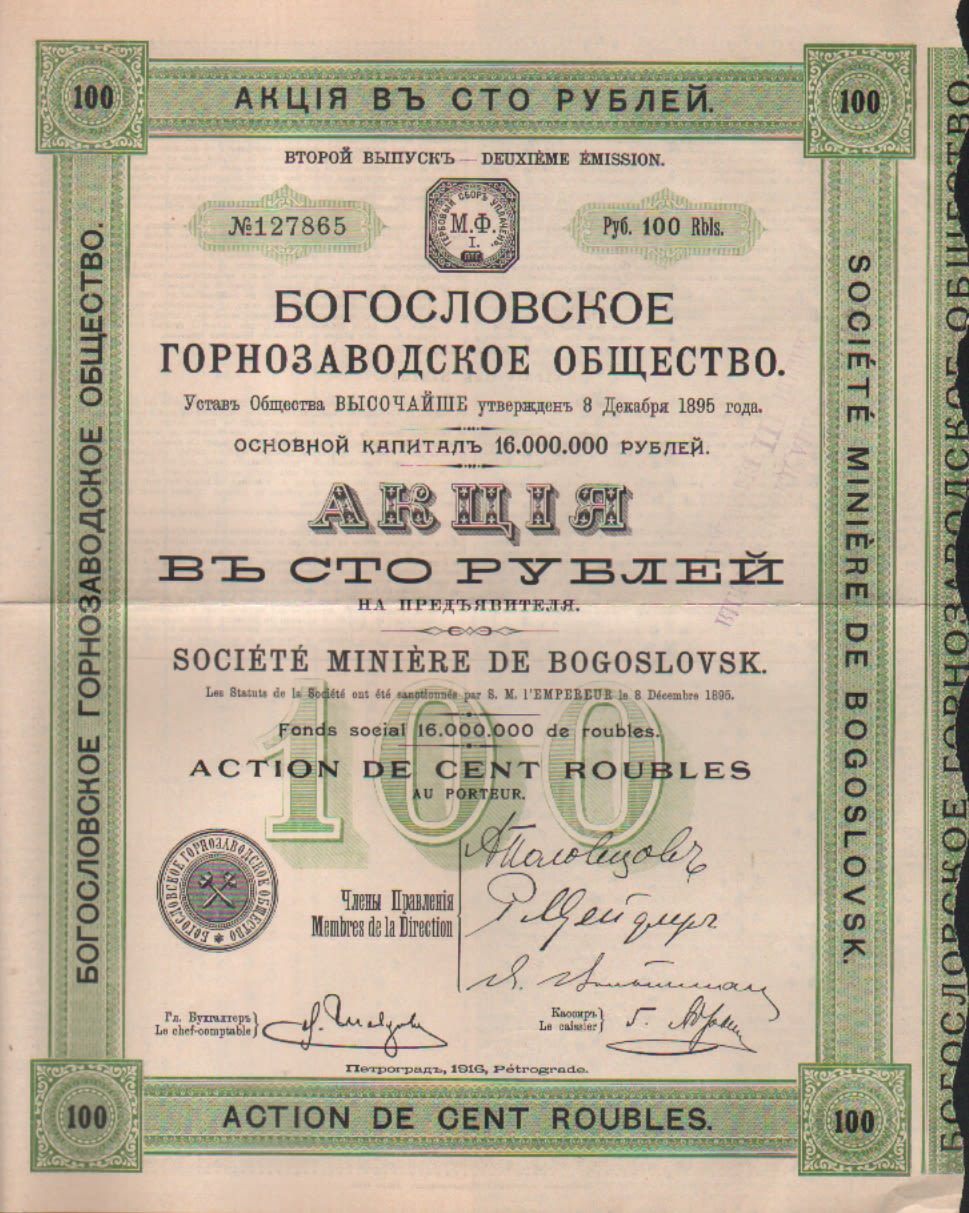

In the 19th century, pig-iron production was closely dependent on supplies of wood fuel: to obtain 60 poods (i.e., 1 ton) of pig iron, 6 m3 of charcoal were consumed. Well-developed navigation on the Sosva River also played an important role in choosing the site for the Sosva plant. It began with the creation of the Bogoslovsky mining district, which shipped its products along the Sosva to the ports of rivers in the Ob basin.

The first settlers of the new plant were skilled workers from the Nizhny Tagil plant and the closed Nikolo-Pavdinsky and Sukhogorsky plants; they were given timber free of charge and allocated homestead plots for building homes.

In 1885 the blast furnace of the Sosva plant was put into operation, and in 1887 the plant produced 18,095 poods of pig iron. The development of cast-iron production progressed, and by 1891 the following had already been smelted: 327,000 poods of pig iron in pigs, 48,250 poods of reserve iron, and 27,137 poods of cupola castings.

At the Sosva plant, pig iron in pigs (ingots) and various cast-iron products were produced. They cast stove ironwork in sizes from an eighth of a pail up to a pail, pitchers, washstands, frying pans, waffle plates for home baking, and much more. They also produced semi-artistic castings: patterned cast-iron doors for Dutch stoves, cast-iron parts for fireplaces. The main product was rails, which were shipped by water along the Sosva and Tavda rivers for the construction of the Siberian Railway.

In 1895 the plant was purchased by A. A. Polovtsev to support the construction of the Nadezhdinsky Metallurgical Plant, and in 1900 the Sosva cast-iron plant, together with the newly built Nadezhdinsky plant, became part of the joint-stock company “Bogoslovsky Mining District”.

The Sosva plant was headed by the managing mining engineer Apollon Vasilyevich Nikitin. He was there from the day the plant was founded and remained until 1900. He was a cunning and cruel administrator who knew how to position himself so that people took him into account and feared him. Nikitin lived as a bachelor, very withdrawn, in a large two-story house near the pier on the riverbank—the best house at the Sosva plant. By the manager’s house there was a large garden with hotbeds and flower greenhouses. The blast-furnace and foundry shops, as well as the pattern shop, were run by P. P. Kashin, an intelligent, capable worker who had perfect command of the pig-iron smelting trade.

In 1905, 756,291 poods of pig iron were smelted and 593,133 poods of various iron products were produced. In 1909, productivity declined; the mechanical shop burned down, and losses exceeded 100,000 rubles.

The plant operated on charcoal and imported ore delivered by water from the settlement of Filkino. The surrounding population of the villages of Mishino, Kiselevo, and others worked in charcoal kilns, supplying the plant with wood fuel. The residents of the settlement of Sosva derived their livelihood exclusively from work at the plant.

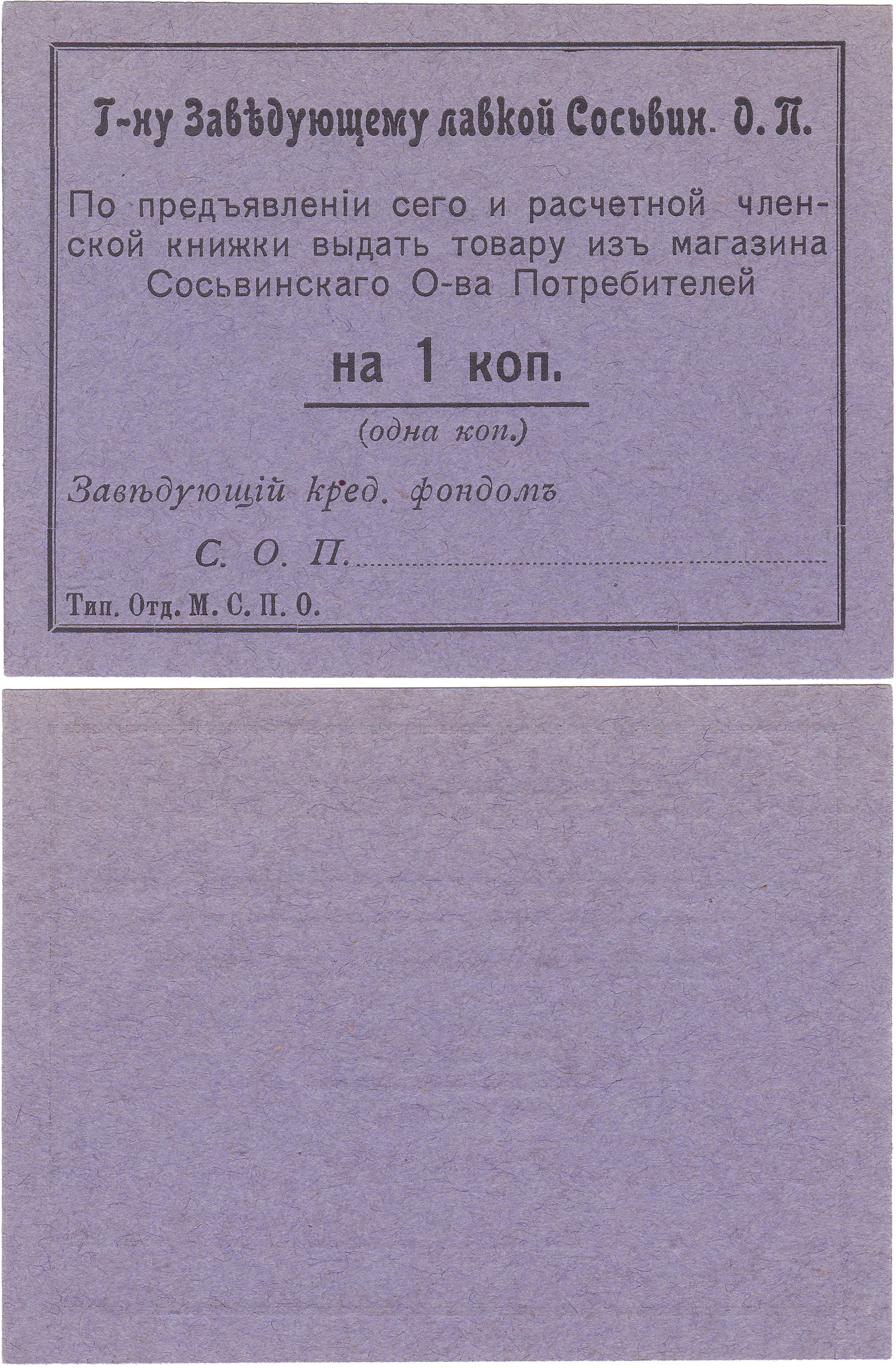

During the plant’s heyday, the settlement had 414 households; in 1890, 5,000 people lived there, with one two-grade school, a hospital, a church, a state-run shop with annual turnover of 70,000 rubles, a beerhouse, two wine cellars, and several shops owned by the merchants Romanov, Ragozin, and Lapin; in addition, brisk trade was conducted in a special shop on the Sosva River. There one could purchase goods against wages, using paybooks. Many residents came to Sosva from the village of Koshay and from other nearby villages. In the shop they exchanged homemade footwear, bed linen, clothing, and towels for imported goods.

In 1899, a consumers’ society was organized, with 300 shareholder-members and an annual turnover of 121,000 rubles.

On March 24, 1918, the plant was nationalized. During the Civil War, production ties with the Nadezhdinsky plant were disrupted. In November 1920, work resumed: they began casting ingot molds for the open-hearth shop of the Nadezhdinsky plant, as well as casting plows, harrows, nuts, and household utensils. In 1925 the plant was shut down and never resumed operations again.