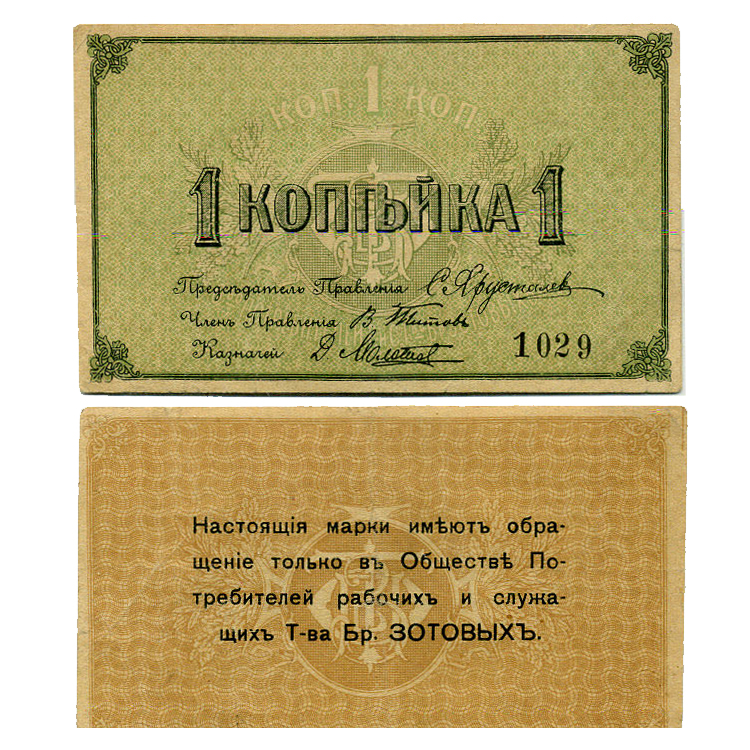

The Consumers’ Society of workers and employees of the Zotov Brothers Partnership was established on September 28, 1895—at the initiative of the factory staff—with the aim: “...to provide its members, at the lowest possible price, various items of consumption and household use, and to give its members the opportunity to make savings from the profits of the Society’s operations.”

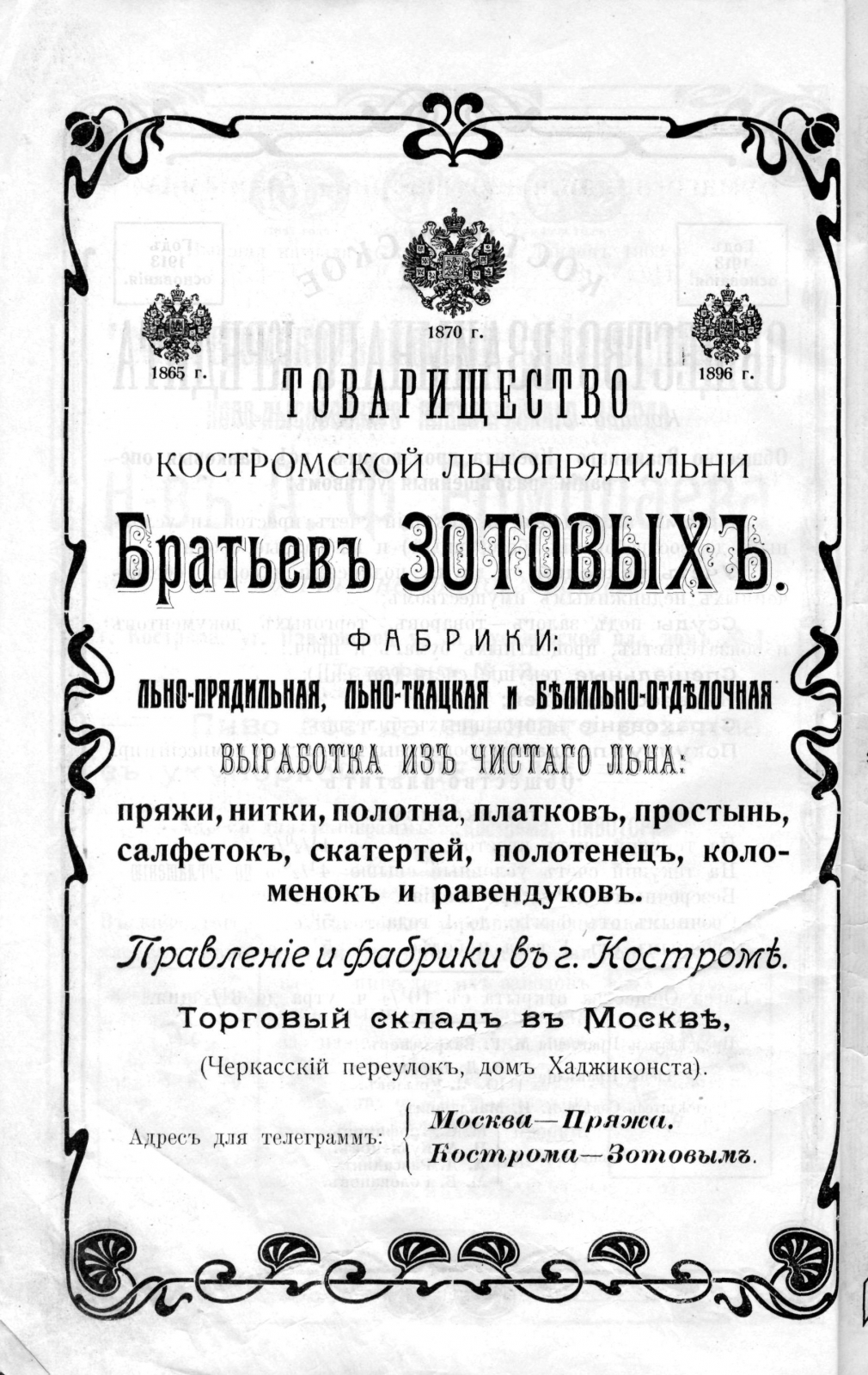

The world’s largest flax-spinning factory, on the northwestern outskirts of Kostroma by the bank of the Zaprudnya River, was founded in 1859 by the Moscow merchant Zotov, who hired as master craftsmen graduates of the Moscow trade school who settled at the factory. Thus began Spaso-Zaprudnenskaya Slobodka, the Zotovs’ factory enclave.

The Zotov industrialists were members of many public organizations. They served as city council deputies, sat on boards of trustees of orphanages and a girls’ gymnasium, performed duties of justices of the peace, and took an active part in the work of zemstvo institutions. This family did much for Kostroma’s lower estates. With their money—both during their lifetimes and later, by bequest—many philanthropic institutions were established. Several schools alone were built in the city. Children of townspeople, peasants, minor officials, church servants, workers, factory foremen, and soldiers studied there.

The enterprise developed intensively. From 1866 to 1880 the number of spindles increased to 13,788, and by 1890 exceeded 52.2 thousand. In the number of spindles it already surpassed the flax-spinning mills of Sweden, Holland, and Denmark combined.

Starting with 32,500 poods of yarn per year with continuous 24-hour operation, by the beginning of the century the spinning mill produced up to 300 thousand poods of yarn with a 10.5-hour working day.

The weaving department also expanded. At first there were 22 power looms here, and by the end of the century there were already 8,687, producing 6.8 million meters of linen cloth per year.

The total value of output amounted to almost 4 million rubles. The manufactory had its main warehouse in Moscow (and a shop on Ilyinka) and branches in St. Petersburg, Kharkov, at the Nizhny Novgorod Fair, in Warsaw, and in Rostov-on-Don. Goods were sold to Moscow and to Yaroslavl, Kostroma, and Vladimir gubernias. They were also in demand abroad. This is evidenced by the “Grand Prix” at the World Exhibitions in Paris (1900) and Turin (1911).

The range of products speaks for itself. The factory produced from No. 4 to No. 160 English counts! Fabrics for underwear, fancy fabrics, canvas for dressing gowns and aprons, other linen goods, as well as canvas for the army, and sailcloth and tarpaulins. One of the first in Russia, the “New Kostroma Linen Manufactory” began producing canvas for paintings.

At first the business was organized as a share partnership. Later, in 1904, the share partnership was transformed into a joint-stock company.

The partnership’s core capital (which in 1891 amounted to 1 million 200 thousand rubles) was divided into shares—5 thousand each. Each share came with a sheet of coupons for receiving dividends over 10 years. After that period, shareholders were issued coupons for the next 10 years.

The most influential shareholders of the partnership were the Tretyakov brothers, with Sergei Mikhailovich being wealthier than his brother. In one letter to I.N. Kramskoy, Pavel Mikhailovich remarked: “By the way, about my means. Not to mention the von Mecks and the Dervizes, in Moscow many are richer than my brother, and my means are six times less than my brother’s, but I envy no one.” This forced P.M. Tretyakov to be extremely frugal, and even to cut his personal expenses and the funds intended for the upkeep of his daughters. And here are lines from a letter to his wife (1892): “I spend on paintings; the goal here is a serious one—perhaps it is carried out not skillfully enough, that is another matter; besides, the money goes to working artists, whom life does not particularly pamper... But when even a ruble is spent unnecessarily—it annoys me and irritates me.” (A.P. Botkina, op. cit., p. 236). He considered, for example, the purchase of a country estate to be wastefulness.

How, then, was the work at the “New Kostroma Linen Manufactory” organized?

The management of the partnership’s affairs belonged to the Board located in Kostroma. The Board consisted of four directors elected by the general meeting of shareholders from among the shareholders for three years. Only persons holding at least five shares could be directors. The Board met at least once a month and exercised full control over production, managing all the Society’s affairs and capital.

In a note to Clause 1 of the Partnership’s Charter, it was emphasized that the partnership’s shares belonged exclusively to Russian subjects. This decision lay in the general mainstream of the Slavophile tendencies of the Russian merchant class and was connected with the desire to establish Russian capital in the leading branches of the economy.

Under the Charter, the partnership had the right “to acquire as property, as well as to build anew or to lease, industrial establishments corresponding to the purposes of the partnership, and also land holdings, the area of which was not to exceed 200 dessiatinas.”

Thus, by the end of the 1880s, a row of flax-spinning factories lined the bank of the Kostroma River. It is hard to believe now, but factory development once shaped the city’s silhouette from the side of the Kostroma River. Great attention was paid to the planning of the factory yard, the variety of architectural forms, and decorative details.

The “New Kostroma Linen Manufactory” was housed in two stone buildings roofed with iron and lit by gas. The flax-spinning building occupied three full stories. The weaving building was a two-story structure with a one-story wing and an annex.

The water required for flax production was taken from the river; for the weaving department and the bleaching works—from a pond. The spinning mill was driven by two medium-pressure steam engines of 80 and 100 horsepower (with 8 steam boilers); the weaving department had one 25-horsepower steam engine with 2 boilers.

Next to the factory premises, over time, an entire factory town grew up: well-appointed dormitories for workers (“House of Labor” or “prefabricated” barracks), which, incidentally, still serve their purpose to this day; a dormitory for employees, a bathhouse, a hospital, a pharmacy, a maternity shelter, a nursery, and a school for the children of workers and employees. All these services were free.

Thanks to the partnership’s support, from 1898 a consumers’ society operated at the factory, where every worker and employee could purchase everything necessary. A specially built shop had three floors: the two lower floors sold foodstuffs (the ground floor—meat, the middle—groceries), and the upper floor—manufactured goods.

The Board cared about workers’ needs primarily because of fierce competition. Merchants poached workers by creating better working and living conditions. For example, the consumers’ society at the “New Kostroma Linen Manufactory” was created at the moment when the factory faced the threat of labor outflow: some neighboring factory owners had already opened such societies.

The factory manager, N.K. Kashin, writes to P.M. Tretyakov in 1896: “I have always been against having my own shop, as well as a consumers’ society, which in any case would give me extra work and take away my time. But now it will be necessary to do it, and to push this matter as vigorously as possible. We will have to use everything within our power to keep our people from moving to Sidorov and Kurochkin.”

Over 10 years, the consumers’ society’s profit grew from 179,318 rubles in 1898 to 535,934 in 1907.

Later this was supplemented by trade in haberdashery, footwear, tableware, and fabrics. A branch was opened across the Volga. A tea shop was opened at the society. In addition, there was something like a club. Thus, not only the material but also the spiritual needs of workers and employees were met.

All this attracted workers to the factory. Production expanded. If at its opening in 1866 the factory employed 748 people, then in 1882—1,800 people (of them: men—600, women—600, and adolescents of both sexes aged 12–18—300). And in 1912 more than 6 thousand people already worked at the factory.

Workers’ pay, monthly and piece-rate, amounted to: men—8–22 rubles, women—7–18 rubles, adolescents—4–12 rubles.

Work was in shifts: 2 shifts of 9 hours. The first shift began work at 4 a.m. and ended at 1 p.m.; the second worked from 1 p.m. to 10 p.m. There were 280 working days a year: besides Sundays and national and local holidays, work stopped from half of Holy Week until Wednesday or Thursday of Thomas Week (at Easter), for the three days of Christmas, and for two days of Maslenitsa Week.

Some of the workers were residents of Kostroma and nearby villages; others were peasants from neighboring districts and from Vologda Governorate. Permanent workers, of course, lived in better conditions: they settled in, and some even set up a kind of their own “income houses,” renting out apartments to anyone interested. In this way the housing problem for temporary workers was partly resolved.

But in general this last category of factory workers (not only at this one, but at all the others) lived in significantly worse conditions. They rented apartments in the nearest parts of the city. They slept on bunks. Single men usually paid 1 ruble for lodging (with meals), and a family—3–5 rubles a month. The premises were in most cases cramped and stuffy. Often, in a room 8 arshins long and wide, 3–4 families lived. They occupied corners and separated themselves from each other with canvas curtains or hung-up clothing.