In mid-1921, the network of communal canteens shrank sixfold, and by the end of that same year, with permission from the People’s Commissariat for Food of the RSFSR, a rapid growth of private cafes, restaurants, canteens, and tea rooms began.

To compete successfully with private public catering, in 1921 a cooperative association, “People’s Food” (“Narpit”), was created. The plan was to feed the population with quality food at low prices. In November of that year, the “Narpit” trade union opened 8 public canteens in Moscow: 2 in the center and 6 on the outskirts. The food really was cheap, but the selection of dishes was sparse and the quality poor. On the other hand, “Narpit” had its own media outlet, “Worker of People’s Food.” It included complaints about service, reprimands for specific discipline violators, and cartoons.

In 1924, factory-kitchens appeared—specially built multi-story buildings with numerous prep workshops. The first started operating in the city of Ivanovo-Voznesensk (now Ivanovo). All equipment was purchased in Germany and the USA, where similar enterprises were already running at full capacity.

In May 1927, the second factory-kitchen in the country opened in Nizhny Novgorod, serving a number of industrial enterprises and schools.

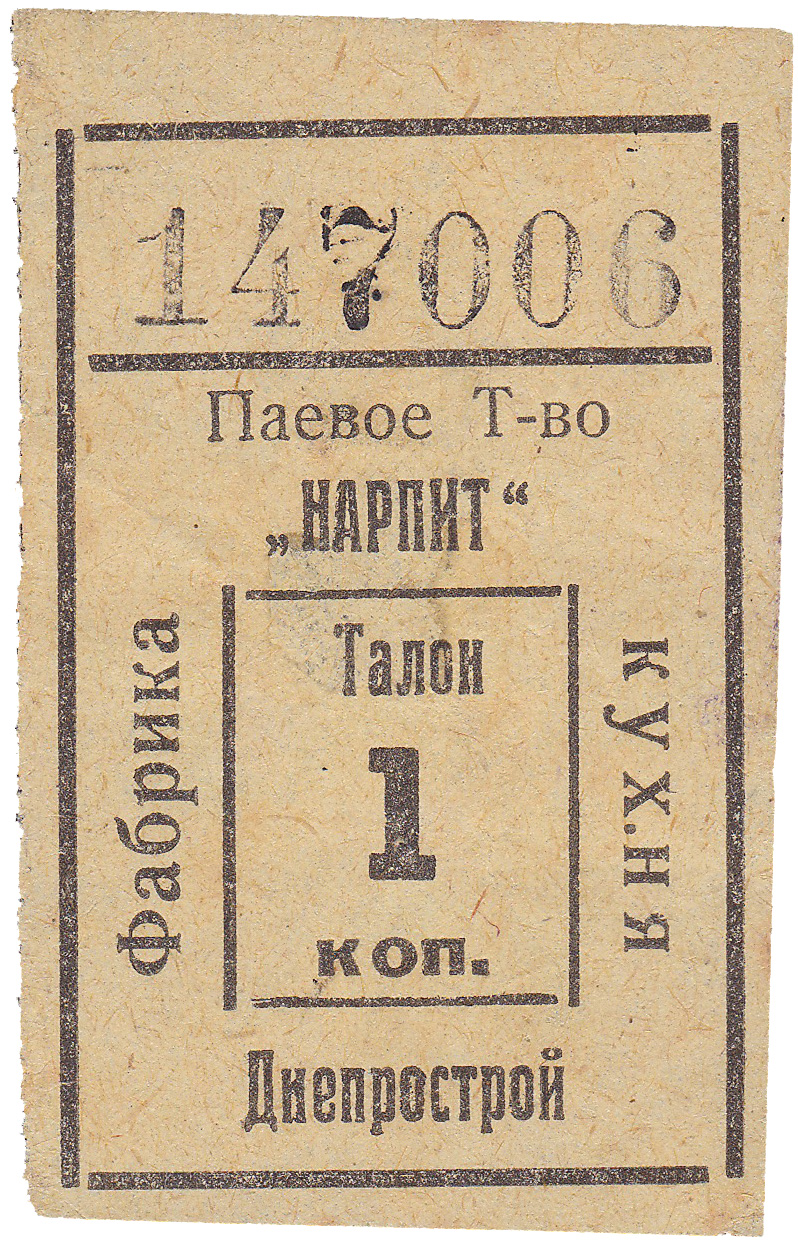

In 1928, at Dneprostroi a public canteen was opened for 8,000 lunches a day. The Dneprostroi factory-kitchen (architects V. Vesnin, N. Kolli, G. Orlov, and S. Maslikh) became the first opened in what is now Ukraine and the third in the USSR. The enterprise fully lived up to its “factory” name—huge production spaces where almost the entire process of cooking, washing dishes, slicing vegetables, and cutting bread was carried out with the help of machines made by the well-known firm “Siemens.”

The productivity was insane as well: 8,000 lunches a day meant 18,000–20,000 different dishes per day! At the same time, the Dneprostroi “canteen” could easily serve as a cultural center—one only had to clear the dining hall of tables.

“In a huge hall with a cement floor, long tables and benches knocked together from warped boards stand in rows, and on the tables—fish bones… In exchange for ration coupons, they brought us soup on carts. Genosse Eliza suppressed a gag reflex and went out…”

Leonid Fuks, “Foreign Specialists”

Yet according to statistics, the desire to eat there was exactly what was lacking—in a day, about 3,000 people ate at the factory-kitchen. And this was with 12,000 workers employed at Dneprostroi and 25,000 people in the general population. Why? The answer from Oleg Vlasov, a senior staff member of the local history museum, is simple: “Because they cooked tastelessly!” “Liquid dishes—watery, without enough vegetables, often completely cold and always bland,” the journal “Chronicle of Dneprostroi” testified in 1931. Things were no better with main courses—for example, meat cutlets that were supposed to weigh 110–125 grams raw, thanks to crafty cooks “lost weight” by a third at once. The same “Chronicle of Dneprostroi” described the results of a public oversight raid on the factory-kitchen with an eloquent phrase: “In the dishes, surprises in the form of cockroaches and dirt began to be found LESS often”!

However, even the few who wanted to taste “cockroaches and dirt” faced a huge problem: in the kitchen, grandly called a “factory,” there was an acute shortage of ordinary kitchen essentials—dishes and cutlery. Enormous lines for ordinary spoons resulted in many absences and people going to work without lunch. They tried to solve the problem in ways typical of that time: confiscating kitchen items from the builders’ barracks and with the help of a church that had fallen out of favor—boilers for the Dneprostroi canteen were made from 32 tons of... bells from the Tver Znamensky Cathedral.

“The factory-kitchen earned itself an inglorious reputation for its confusion, the arbitrariness of its administration, the rude treatment of visitors by staff, the lousy quality of the prepared food, unsanitary conditions, and more,”—there is, unfortunately, nothing to add to this conclusion of the “Chronicle of Dneprostroi.”

Memorandum from an employee of the American Consultation, Z. L. Myers, to the Deputy Chief Engineer of Dneprostroi, P. P. Rottert

I hereby bring to your attention that I am dissatisfied with the food I receive at the factory-kitchen. There is no white bread, no coffee at 6 a.m., and the omelet is served with pieces of eggshell. Please pay special attention to white bread.

The first Moscow factory-kitchen appeared in early 1929 on Leningradskoye Highway, building 7. A glass-and-concrete avant-garde building was constructed специально for it, based on a design by architect A. I. Meshkov. In the second half of the 1930s, the building was converted into the “Sport” restaurant.

Once there is a factory-kitchen, then to control large volumes of perishable products (meat, fish, milk, eggs, fats) new specialists are needed: epidemiologists, toxicologists, food sanitary control staff, and dietitians. In laboratories, they monitored caloric content, the levels of vitamins, fats, and other macronutrients in prepared food, often taking into account the specifics of particular professions, for example, metallurgists or miners.

The speed of cooking is another distinguishing feature of these food combines. William Pokhlyobkin wrote: “If at home each housewife spends at least two hours preparing lunch, then preparing a standard lunch at first-generation factory-kitchens in the 1920s took 2 minutes.”

A daily set (three meals a day) at a factory-kitchen canteen in those years cost 88 kopecks with an energy value of 3000–3100 kcal. A month of normal meals cost 27 rubles, with the average salary of a skilled worker at 185–200 rubles, an engineer at 230 rubles, and a cleaner at 95 rubles.

Where did such penny prices come from? The cost of products and production expenses were covered 60–80% by the state or by the enterprise served by the factory-kitchen, so the canteen customer paid 20–40% of each dish’s cost.